Leyla Stevens: Diaspora Pavilion 2 Artist in Conversation (Transcript)

9 Jul 2020

People:

Project:

Location:

Online

Artist Leyla Stevens speaks with curator Jessica Taylor about her practice and participation in the upcoming exhibition ‘I am a heart beating in the world: Diaspora Pavilion 2, Sydney,’ which will be presented by International Curators Forum in partnership with 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art in 2021.

Watch Video

_________________________

Jessica Taylor: Good morning from London and good evening from Sydney. My name is Jessica Taylor and I am the Head of Programmes at the International Curators Forum, and one of the curators of the exhibition ‘I am a heart beating in the world,’ which forms the first part of the Diaspora Pavilion 2 project, an exhibition that will take place in Sydney, in partnership with 4A Center for Contemporary Asian Art, and will feature the work of six artists based across the UK, Australia and the Caribbean. And I’m thrilled to be joined by one of the artists today.

Joining us from Sydney is Leyla Stevens who is an Australian Balinese artists and researcher who works predominantly with moving image and photography. Her practice is informed by ongoing concerns around gesture, ritual, spatial encounters, transculturation and counter histories, working with modes of representation that shift between the documentary and speculative fictions, her work deals with a notion of counter archives and alternative genealogies.

So, our jumping off point is going to be the notion upon which the project departs, which is diaspora. And I’m wondering Leyla, if you could just speak a little bit about how you engage with diaspora, both as a concept and a lived experience in your work and in your practice.

Leyla Stevens: Well, first I’d like to acknowledge the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation whose land I’m currently speaking from today, acknowledging that it is unceded land and pay my respects to the elders past, present and future.

In terms of diaspora, well, it has been a relatively new thing, I would say it’s a relatively new concept that I’ve been engaging with in my work. I mean, it’s always there obviously as a sort of background to the work and how I experience and view things. But I think for me growing up, you know, I was really sort of unconnected to the Indonesian diaspora in Australia.

You know, so my Balinese heritage was really quite othered from an early age and all my Balinese family were in Indonesia. They were in Bali, they weren’t in Australia. So, my sense of identity was really split between the two places, which is probably a really common experience of the diaspora, so these two disparate places and cultures and homes. And then it’s only been really recently that I’ve been able to sort of frame diaspora as a sort of critical framework to the work, because I’m making work that responds to specific histories in Bali and a specific history of place. So, it’s been quite interesting to see how the work has been received in Indonesia. I’m really sort of understood as an Australian and mixed Balinese heritage artist in Indonesia, and that sort of shaped the reception of the work. Whereas I think conversely, some of those complexities are sort of lost in Australia when I share the work here too.

Jessica Taylor: To give it a bit of background, some of the works that we’re going to be speaking about today, most of them were filmed in Bali. And one of the things that I’m particularly drawn to is the way in which you bring together really remarkable captured footage of the natural environment and natural landscape in Bali and very personal, very delicate human stories. I’m interested in this relationship between the figures that you present and the natural world. Can you speak a little bit about that relationship?

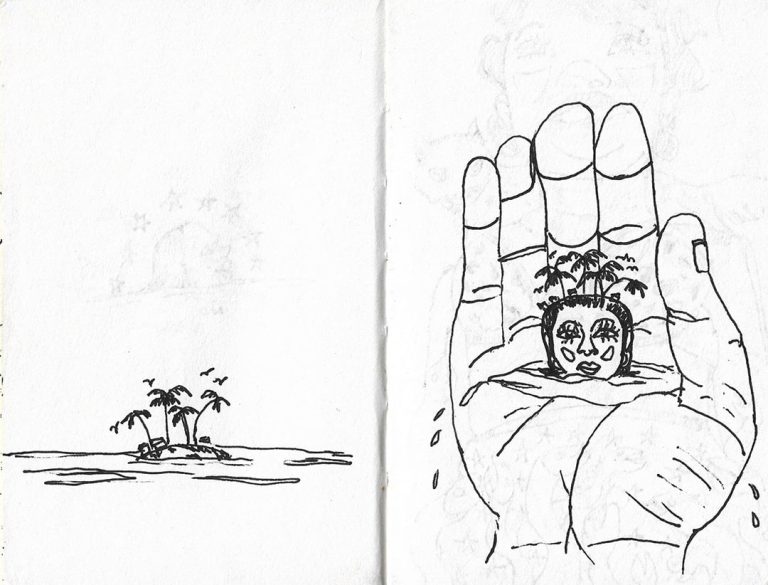

Leyla Stevens: I’ve always sort of been responding to the natural landscape, a lot through my work, and a lot of this sort of extends out of a background and interest I have in landscape modes of photography and lens-based practices. And a lot of it, especially in terms of context of Bali, really responding to image histories around Bali and how it’s been especially exotified in colonial and Western representations. So, a lot of the way that I cite landscape in those works that you’re familiar with as playing with that kind of representation around Bali, it’s this kind of narrative. I call it the peaceful Island narrative that shaped Bali throughout different areas. And so, I was always interested in kind of working with the landscape in that way and complicating it. I use a lot of ocean images in my work, a lot of coastal scenes, a lot of scenes with coconut fields and beaches. And I’m really interested in these sorts of landscapes, how they’re culturally symbolic. And how that’s been checked through image representation as well. So, especially in Western image traditions, the ocean is either a sublime or narrative kind of space, it’s this kind of emptiness. Whereas I’m really interested reclaiming these perspectives of the ocean, as this sort of really culturally networked space. It’s a big connector rather than emptiness between landmasses. And this really significantly shifts how islands are represented and thought about in terms of scale. All of a sudden, they become very big rather than very small. I’m exploring that with these reoccurring ocean images.

Just thinking about Balinese perspectives around the ocean as this really sort of powerful space traditionally thought of as a dangerous space. And the water’s really important for a lot of the ceremonial rituals that we do around the ocean – we throw our ashes during cremation rituals into the ocean. So, this is sort of at odds with the peaceful Island narratives, where the ocean is a space of leisure and the beach is like a sort of pleasure place or tourist capital. I’m interested in exploring these counterpoints and their representation of landscapes. And I am responding to these kinds of sensitive political histories and repressed histories of place and the problem of representation comes up. How do you represent something that you can’t see and how do you represent something that has been surrounded by this sort of politicised amnesia? There’s sort of no reference points in the landscape to these histories. So, one way of doing that is by presenting these slowly unfolding landscapes where you start to pay attention to what you can’t see in the image.

So that’s where I think of these nature images are quite important. Especially in Bali, because they’ve been invested and thought in that way for a long time. There is this philosophical concept in Bali called Niskala, where it names the unseen or the immaterial histories and archives in place.

Jessica Taylor: So, we’re speaking about two films in relation, A Line in the Sea and Kidung. And I’m wondering if you could give a short introduction to both films?

Leyla Stevens: A Line in the Sea is a three-channel work. A feminist retelling of a cult film that was made in Bali in the seventies called A Morning of the Earth, which was really instrumental in terms of initiating early surf narratives in Bali. So, if you speak to any older Australian surfer, most likely the reason that they went to Bali in the seventies and eighties is because of this film. And in the film, there’s no spoken narrative, the camera just follows these two white surfers as they walk through the landscape and, and then they go into the ocean and the surf. And I was interested in what that did, I really saw it as this kind of discovery narrative. They were implementing and they were laying down their own narratives about Bali through these really simple gestures. So, I thought of a way to reclaim a bit of a trans-cultural perspective and show what has been the legacy of that film and that tourism, in that actually Indonesian woman now surf, which was unthinkable in the seventies. So, to show it from their perspective and show them sort of recuperating a feminist perspective within that surf narrative.

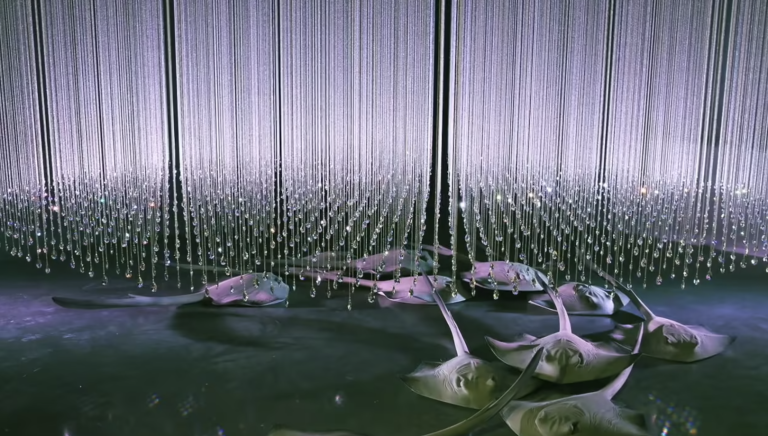

And Kidung is a three-channel video work and it responds to a site where a mass grave from 1965 lies in Bali and on this site lies a banyan tree. So, I really think of it as almost as a sort of central character in this history and it’s a kind of witness to those events. So, two of the channels essentially are portraits of the tree itself and close ups of the tree. And in the central panel, we see a woman chanting a lament and she’s chanting in this traditional ceremonial style of chanting that’s done in Bali. And it’s a single shot of her, a continuous shot and of her singing towards the tree.

Jessica Taylor: I’m really drawn to the ways in which you channel personal experiences and memories as a means of exploring these moments in history that you spoke about. Can you detail a bit more, how you merged documentary with speculative narratives or storytelling in your work, and perhaps also speak about this process that you wanted to go through research and writing and then visualising for a film?

Leyla Stevens: For this project Kidung, because it was responding to such a specific and contested history, the research phase was more involved and I do draw from methods that are kind of more, I guess, sort of ethnographic in a way. And then I do do a bit of field work. A part of it is talking to people and interviewing people and actually looking at and engaging with existing archives. So that’s the background to the way of making work.

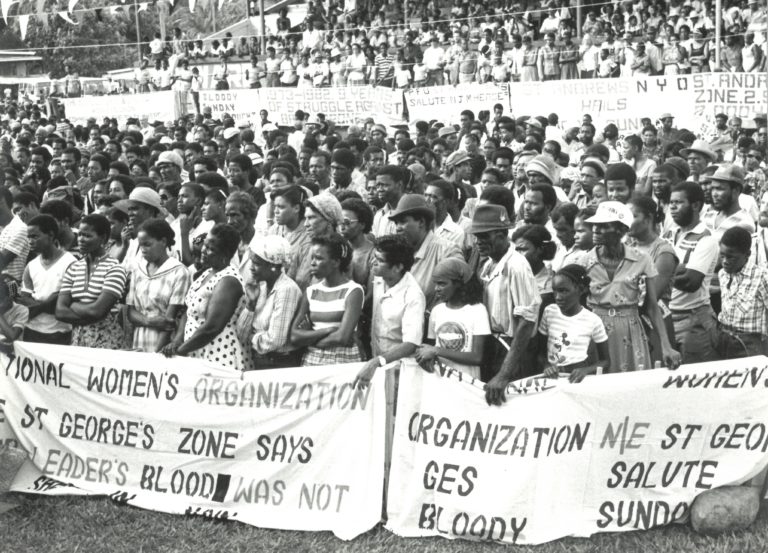

Especially in this case, to give a bit more context – The genocide of 1965-66 in Indonesia has been really covered and a really prevalent theme more recently with artists and in academia, but I think outside of these intellectual and progressive circles, it’s still this really taboo history. We can take for granted that we’re speaking about this now over a public Zoom, but it’s still not possible in many parts of Indonesia. So, part of my process is to learn a little bit more about the Balinese context to this history and how it’s played out there and to speak to either survivors or people who had family members killed during this time in Bali. And it was a really powerful process. For many people, it was still a source of something that has been so silenced and, in some cases, even a source of shame in their family history. So there still exists a lot of rhetoric or vilification of communists in Indonesia.

And that’s still a sort of dominant narrative. So, uncovering these stories really felt important for me to do before I made the video works, as a sense of knowing how to tread lightly through these histories. And then the process of making, I mean, as you say, I like to work with these sort of more documentary genres of filmmaking, and then I insert these more stage performative elements in there. And it’s actually quite a really loose process. I know the outcome looks like it’s mimicking this kind of filmic structure, but actually what I do have is a bunch of scenes that had this kind of feeling that I know what I want to do. And sometimes it’s really simple where it’s just a sort of conversation between a subject and a landscape, and we go from there. So that’s why I used these techniques, like the long shot, where I leave the camera recording with a hands off direction, for five, ten minutes worth of footage – where I can walk away and just let it settle, let the subject be in front of the camera.

So again, it’s sort of a tension between something that’s staged and then something that’s just observed or documented in the landscape. And also, it’s a really collaborative process, that’s something I really enjoy. So, I’m not only talking and learning, but it’s also working with local collaborators and performances. So that’s really a nice collaborative process.

Jessica Taylor: And while in A Line in the Sea you prioritise this unspoken relationship between the two surfers in the film and the shoreline and Bali as they traverse it, in Kidung you depicted the performer chanting, as you mentioned. And am I right in thinking that you wrote that lament relaying your father’s memories of watching the burial of the bodies during this moment in history that you spoke about?

Leyla Stevens: It was actually translated from a script that I wrote for an earlier work called Their Sea is Always Hungry, which was a single-channel video. And in that video, there was this two-person dialogue between these two voices that we hear in the writing. And this questioning dialogue around 1965 and Bali, and some interweaving of lots of different sort of moments in history, showing this multiplicity of memory around 1965. So, one of the voices in that was a performer called Cok Sawitri, and she is a writer and poet in Bali. And she is also from the older generation of experimental performance practices in Indonesia. And I had heard her perform this kind of style of Balinese ceremonial chanting before and I asked her if she would be willing to collaborate on a script with me and do it in context of 1965. And what she did instead was to take that script that I had written for Their Sea Is Always Hungry and create a kind of singular narrative out of that and translate it into a sort of form formal version of Balinese.

I framed it as a lament to the banyan tree and the memory of those missing dead there. And I intentionally ended up not putting subtitles in. So even for a majority of Indonesian audiences who weren’t Balinese, they were not understanding the specifics. But I think what was important for me in that work was really the emotive value of what she’s singing and how she’s singing. So, the decision to not do subtitles, I stand behind it in the end.

Jessica Taylor: I was thinking about that when I was watching the film again recently, because it’s such an emotive experience watching her. She seems very introspective, even this moment where Cok pulls out a cigarette and she starts to smoke mid chant, you feel like she’s looking inwards. There’s a strong sense of emotion as she does it. So, I think this relationship to language and the decision not to translate the chant was really powerful.

And I get that, in your work, it’s this focused on gesture and image that seems to take priority over language. But I do think that even though we don’t have access to it, what’s being said in the chat, this process of writing for me, really sticks out this process that you would have undergone to produce this chant and to write it and to go through this telling in a way that perhaps is not understood, but suggested.

Leyla Stevens: Yeah, the idea of really asserting using spoken voice and singing in that in the work, I think it’s so important in terms of this history, because so much that history was this silencing of voices. And I really wanted to reclaim the voice as a way to speak to marginalised memory and also especially women’s perspectives. So, it’s only women’s voices that are present in the work that I’m showing. So that was important to me.

Jessica Taylor: You were speaking of what about the three-screen installation of the films at your last solo show, which was last year. I’m also curious about your inclusion of sculpture in your installations, these kinds of traces that you leave in and amongst the screens. And I’m wondering if you could speak a bit more about that – the meaning of those objects and those decisions when thinking about installation.

Leyla Stevens: I don’t have a sculptural practice and if I’m honest, it’s a language that still always feels uncertain to me unlike lens-based practices. But I am interested when I’m showing video in a gallery context to really think about it as this kind of immersive experience and to really think about the materiality of a video. I think often when you’re making it, you sort of forget that people are going to be encountering videos as material objects when you walk into a gallery. So, when I introduce sculptural objects, they really are in relation to or an extension of these lens-based narratives that I’m presenting.

I think the one that you’re referencing in that show, I placed in front of that film sprouted coconuts that were on the ground placed on Chinese ceramic platters. I am interested in extending the archive of this Island paradise imagery. Coconuts are sort of an obvious one. And coconut imagery is really prevalent in that film. But also, because it was connected to a 1965 memory – I was drawing upon a story that my father had told me where during the anticommunist regimes, his grandfather owned a tuak store and tuak is alcohol that’s comes from coconuts. And he remembers being a boy and seeing these men arriving or coming to the tuak store after going out and killing squads. He describes this sort of energy that came from these men’s bodies, it was very frightening. So, it was like electricity and it’s an image that really stuck with me – this idea of tuak or coconuts as another archive of this history. So, I’m really interested in material histories and I’m interested in things that present a kind of counterpoint, so we can think of coconut as relating to island paradise images, but you also had this sort of story or the counterpoint of political violence. So that’s where that comes from.

Jessica Taylor: You recently shared with me a film that you made during lockdown titled Scenes of Solace – and I wanted to ask you about the archival footage that’s in that film. You’re speaking about the material life of film, and revisiting of some of these objects, can you speak about the archival material that you use in that film? And I have noticed in a few films as well, that not only do you revisit subjects, but also sometimes imagery from previous works. Can you speak about archive and how that manifests in your work?

Leyla Stevens: That whole work is investigating the archive, not only of my own practice, where I reuse images and kind of shots from past, but also, I drew a lot from past archives, from family videos and footage. The archives in that work were actually given to me by an Australian surfer who was passing through Bali in the seventies who shot a lot of super eight footage and he had reels and reels of it. And he gave me some of these reels and because he knew that he had documented my family and the compound, and it was crazy to get it digitised and see these images of my aunties and my cousins and my grandparents all through the eyes of a complete stranger passing through in the seventies. It was quite bizarre. It really was this sort of archive that was out there, and I got to reclaim it and have a look at it.

Jessica Taylor: That’s wonderful. What a nice thing to have. It’s like you say, the perspective is a twist perhaps, on these very personal images.

Leyla Stevens: It’s very strange seeing video of your parents when they were 19.

Jessica Taylor: Shot by a stranger that you don’t really know. One thing that I wanted to ask you about was titles. We were speaking about your solo show – and the installations for that show – which you were just describing for us, called Their Sea is Always Hungry. And as soon as I read that title, I was grabbed by it and I wanted to know more. Could you speak a bit more, particularly about that title because I really want to where that’s from, but also your process of titling in general.

Leyla Stevens: It’s actually in reference to a line out of Wallace’s Malay Archipelago. He was the sort of counterpart to Darwin and he was almost getting there with his own theory of evolution and he was kind of on the tailcoats. And he was looking at natural history around what is now Indonesia and Malaysia. And there’s this line when he gets to Bali and he’s trying to get into Bali and it’s this really rough ride and he arrives on a beach somewhere. But what’s really striking about the Malay Archipelago is that it kind of reads like a travel narrative and that’s interesting too. Anyway, he’s speaking to a fisherman who says, “the waves are always hungry here, catches everything and wants to eat them.” So, it’s also referencing one of the deepest ocean straits in the world, between Lombok and Bali and that’s where the Wallace line draws through. So, it’s kind of the split of the flora and fauna of the natural world.

So again, just sort of looking at these travel narratives around Bali, Bali’s full of it. It’s had this whole history of global flows and it’s been really interesting how it’s still represented as this is kind of isolated, culturally authentic sort of place. Whereas in reality it’s always been informed by these global flows.

Jessica Taylor: And we come full circle back to diaspora.

Leyla Stevens: Yes.

Jessica Taylor: And I suppose my last question is about what you think might come next, any insight into future projects or things that you’d like to do or ideas that are percolating?

Leyla Stevens: Well, we’ll see with the current situation, but currently I’m going to start looking at a new project that responds to a certain collection in the Australian museum. Looking at Balinese painting around a specific period that looks at colonialism and modernism. I’m interested in looking at marginalised female painters from this time. But also, female muses from this time. So, there was this real sort of history of European male painters coming to Bali and marrying Balinese woman or having Balinese women as muses. And I’m kind of interested in looking at that.

Jessica Taylor: I can’t wait to see more. Thank you so much for chatting with me today. It’s wonderful to meet, even though it’s only digitally at this point, I can’t wait to be together in Sydney next year to make the show happen.

Leyla Stevens: Absolutely. I’m looking forward to it.

_________________________

Disclaimer: Due to disruptions in the audio recording of the conversation there may be slight discrepancies in this transcription.

Explore Further

Explore Further