Dhelia Snoussi

“How To Get The Local Authority To Do What You Want”:

A 7-Step Guide

When the Westway was built, protests from residents of Walmer Road and Pamber Street made international headlines, drawing attention to the impact of large-scale infrastructure on local communities. Yet the architects had given no consideration to how the land beneath the motorway might be returned to public use.

Photographer Adam Ritchie, newly returned from five years in New York’s Lower East Side, brought with him inspiration from grassroots action he had witnessed there. In Tompkins Square, he had seen local children transform a mound of earth — excavated for theatre construction — into a makeshift playground. When the city tried to remove it, mothers and children formed a human chain to protect it. In the end, the Parks Commissioner allowed the play space to remain.1

In North Kensington in the summer of 1966, Adam saw something similar unfolding on the land cleared for the motorway. Temporarily occupied by the London Free School, the site was due to be vacated once construction resumed. At the group’s final meeting, Adam called for volunteers to keep the emerging playground open.

The site had been left in a rough state — dumped on by contractors and fly-tippers — but Adam and others argued that this land should be repurposed as restitution for the disruption the motorway had caused.

What began as a small campaign to save the playground grew into a broader movement to reclaim all 23 acres beneath the Westway. Adam went on to co-found the Motorway Development Trust (originally the North Kensington Playspace Group), which successfully pushed for the creation of the North Kensington Amenity Trust — now known as the Westway Trust.

(Adam:)

I'd lived near North Kensington from 1960 to 1962. I went to New York for some years. When I came back in 1966, the houses had been cleared and a friend of mine got permission to use the land where Westway was to be built as a playground, and he started the London Free School.

The kids there were building pretty nice things out of the rubble from all the houses that were demolished to make room for the motorway. I deposited a saw, a couple of hammers, and some kilos of nails, which I hid under the rubble. I brought some friends around to see the amazing houses these children had built. But when I arrived, what I'd described wasn't there anymore. There were five other houses – bigger and better. The children made really imaginative structures so I just got very excited and motivated to do more because I thought the London Free School was about to close down. So at the last meeting, I said: "I'm really interested in getting that space as a playground when the motorway is finished."

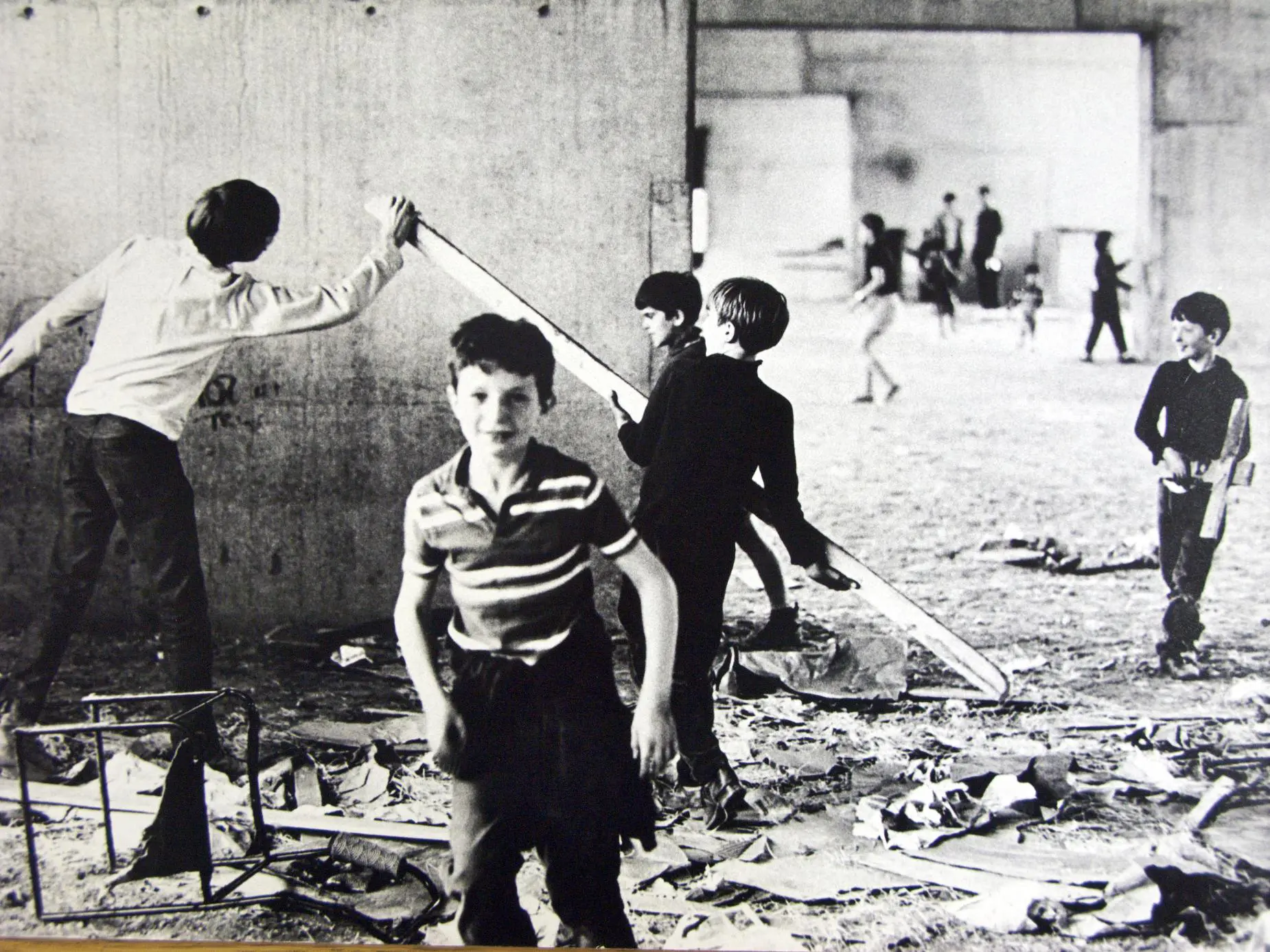

Children playing underneath the motorway creating play structures from the rubble. Source: Adam Ritchie

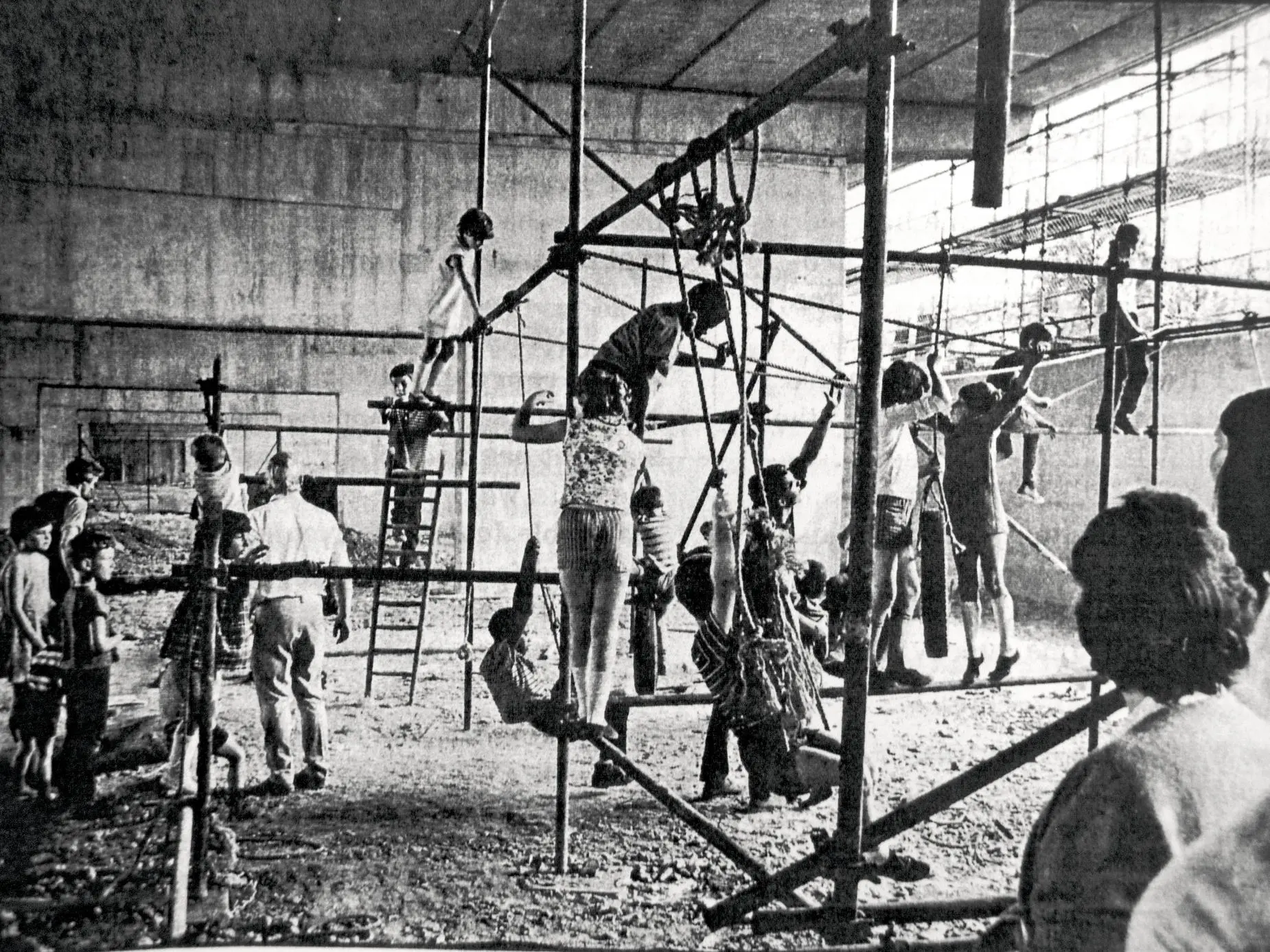

Children playing on scaffolding underneath the motorway. Source: Adam Ritchie

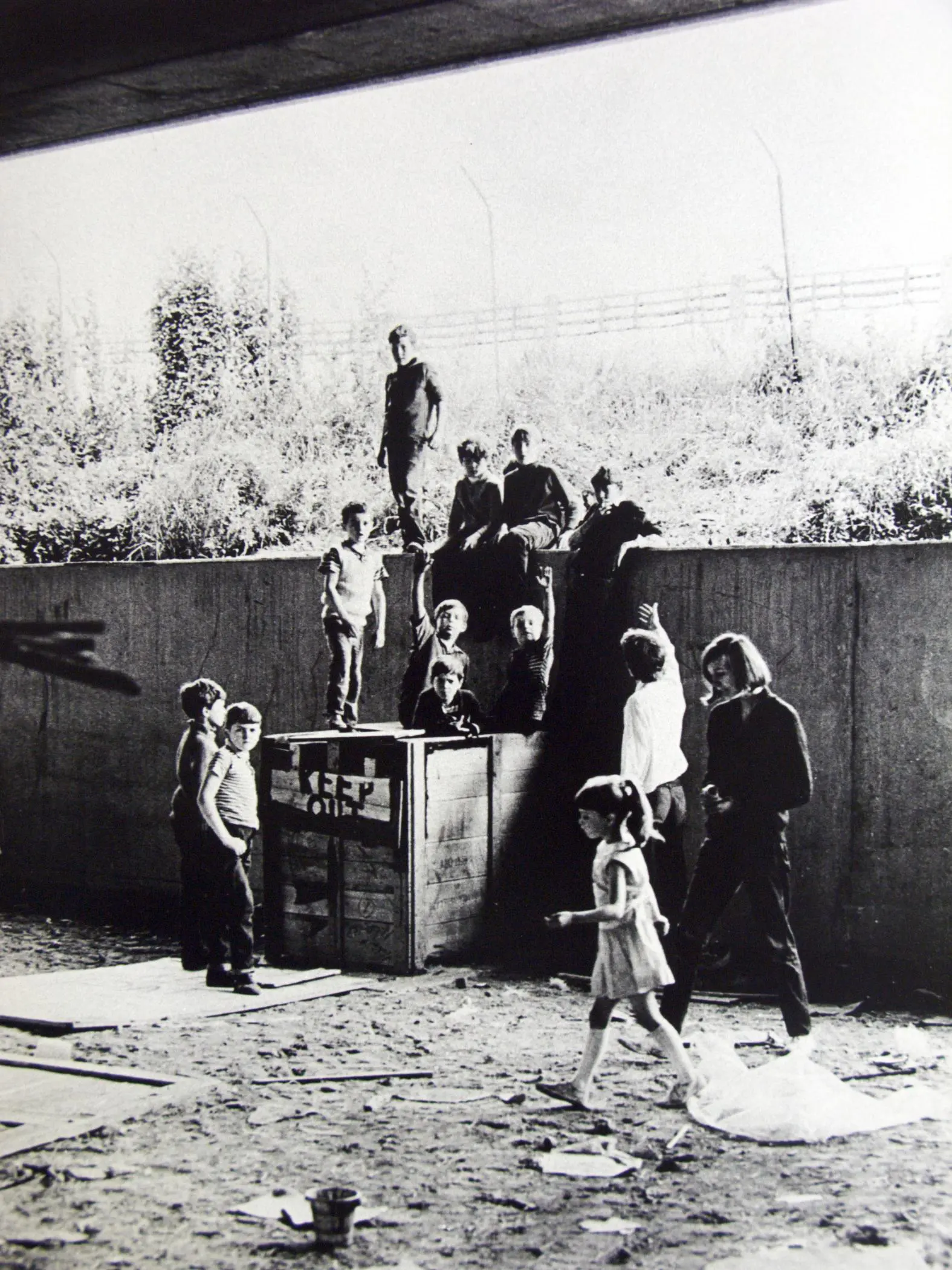

Children playing under the Westway. Source: Adam Ritchie

(Dhelia:)

What was the mood of residents when the Westway was opened?

(Adam:)

I can't think of anything equivalent. You don't have any power. For many residents, the mood was one where: things happen, and you don't like them, but they were building it and you have to accept it.

(Dhelia:)

So your involvement started through the playground. How did it grow from there?

(Adam:)

There was a chance for a playground if it was campaigned for. So we put the idea to the GLC (Greater London Council), who owned the motorway land. Seven or eight of us got involved, including John O'Malley, and we became the Motorway Development Trust. We met weekly for several years. I worked closely with John O'Malley, who knew much more about the conditions in the area. We got 120 volunteers from all over the country – nearly all students – to help run a play scheme in the summers of 1967/1968. Part of that was to do a housing survey.

(Dhelia:)

Tell me about the housing survey.

(Adam:)

Through the housing survey, we realised that North Kensington was really badly housed and overcrowded – and the council had no plans to do anything about it. In South Kensington, people had one tenth of an acre of open space per person, but in North Kensington, there were 1300 kids in a small area from Golborne down to Westbourne Park Road, and there wasn't a single place for them to play. But it was of no interest to the council. They didn't give a shit about the people in North Kensington, but they’d be laying down flower beds at every street corner in South Kensington. It was really an attitude which infuriated me. South Kensington had the same rubbish collection as North Kensington but the density of people in North Kensington was much worse. Then they would say how dirty the people were in the north. That level of callousness just floors me. I'm middle class and their attitude really got to me because you couldn't get them to care at all. They just didn't seem to have any feelings for human beings.

Anyway, as soon as we discovered more about the deprivation of the area, it was obvious the whole 23 acres should be used for the community. Not just the playground space.

Acklam Road before the Westway. Homes have been compulsorily purchased and cleared to make way for the motorway. Source: Adam Ritchie

(Dhelia:)

How did the project grow then, once you realised the need was much greater?

(Adam:)

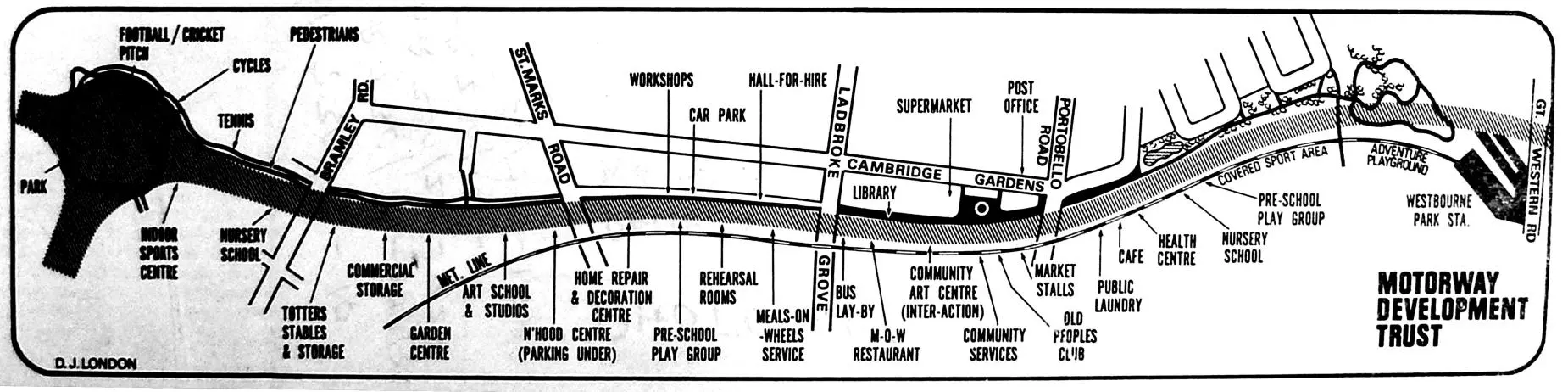

We had public meetings with the local community to say, "What do you need in this area and where do you want it?" And from there, we enlarged our initial plan from just a playground into an eight acre plan. And then eventually we expanded the plan to include the full 23 acres because it looked like the need was gigantic. By the end, we had a 15 foot-long plan of the motorway, which we used to stick up on panels at public meetings. We took all the results to Kingston University’s architecture department who got their students involved and they produced some quite nice drawings for how we could use the space under the motorway. Because of that, we were beginning to get quite a lot of articles in national newspapers and architectural magazines. We really pushed everything on every level.

A 15 foot long plan by the Motorway Development Trust for amenities to be developed under the 23 acres. Source: Adam Ritchie

(Dhelia:)

From that workshopping process, was there anything that emerged most strongly as a need? Was there any particular amenity that people were really keen on?

(Adam:)

There was a range. People wanted play space, they wanted workshops, they wanted studios, artist spaces. They wanted community centres, they wanted nursery centres. They wanted a laundry because people didn't have washing machines then. It was just a huge range of things needed.

(Dhelia:)

So when did the GLC begin to take notice?

(Adam:)

Well they didn’t at the start, and then finally they said we could have a meeting with the heads of the Planning, Transport and Parks departments.

The day before they said, "Is it just you and John O'Malley coming?" I said, "What? No, we're bringing some advisors.” We ended up bringing the Director of Architecture of the Festival of Britain, Sir Hugh Casson, who was later the president of the Royal Academy, and who gave advice to six cities around the world on planning. This town clerk had no idea it was going to be like that and we were going to bring some ammunition. It was much more professional than they expected from North Kensington.

(Dhelia:)

I can imagine the confusion on their faces. What was their response like?

(Adam:)

Well, we gave them the pamphlet with the list of people supporting us: The Bishop of Kensington, Lady Allen of Hurtwood, just lots of people. MPs and things, quite a solid list. They were really taken aback. We also had a letter in The Times and a half page in the Guardian saying this was a really imaginative scheme.

And they replied, "Well, I'm sorry, but we're going to put a car park underneath, eight acres of car park." They said the plans couldn't be altered because they had already been granted planning permission.

I rang a clerk of the GLC to say, "Could I see the minutes where planning permission was granted?”, and there was a big gulp. The reason we knew that it was a lie was because someone called Donald Chesworth, had said, "I was on the committee that year and I don't remember a planning permission being granted.”

(Dhelia:)

I've had small wins in campaigns but that must have felt like such a monumental achievement.

(Adam:)

We operated on so many levels. We influenced people who might have the ear of the people with the power. I had tea with the sister of Sir Malby Crofton (then Leader of the Council) and explained the project to her.

(Dhelia:)

You were persuasive and managed to get yourselves in these rooms with influential people. What about direct action though?

(Adam:)

There was a meeting at All Saints Church Hall, where we invited the Head of the Housing Committee, Councillor Baldwin, to come and explain the council housing policies to the community. He said, "Well, if you don't like living here, surely you just move away.” The people locked the doors of the hall and wouldn't let the councillors leave. There wasn't any criminal damage being done, except kidnapping.

(Dhelia:)

This famous meeting – I’ve heard so much about it.

(Adam:)

The councillors were let out eventually. But the idea was to make them understand what it was like having no way out, which was the case of many poor families in the borough who were living overcrowded in one room.

(Dhelia:)

Let’s go back to the GLC for a moment.

(Adam:)

Yes, the GLC eventually agreed to what we proposed. Unfortunately, Labour had been defeated, so it was a Tory GLC. They gave the land underneath the motorway to Kensington and Chelsea Council, who were very suspicious of anything in North Kensington. Sir Malby Crofton, the Leader of the Council, thought we were all street-fighting communists. He was terrified. Nonetheless, they eventually agreed to create a new body that would manage this 23 acres and deliver our plan. This new body would be called the North Kensington Amenity Trust (NKAT). But Malby Crofton wouldn't let John and I (who put forward the whole idea) sit on the newly-founded Amenity Trust.

We discovered that when it was given to the Council, Sir Malby Crofton, was tasked with writing the NKAT’s constitution. He would choose the chair, he would choose six of the people on the board. He had total control of every single part of it. We took it to the Charity Commission, who agreed with us that it was poor governance. So he had to rewrite the constitution a bit, but still the secretary of the Amenity Trust was the town clerk, the treasurer was the borough treasurer, and so on.

In the end, we forced our way onto the board by being elected as representatives of a couple of local organisations, which Malby Crofton considered safe. We got on the board, but it was like arguing with brick walls. It was really difficult.

(Dhelia:)

Your plan was accepted, partially, so then what were those arguments about?

(Adam:)

Well, anything you proposed, they'd say there was no money. They were very imaginative in not having any imagination whatsoever, so anything could be rejected. But John and I ran seven or eight adventure playgrounds in two summers, and we got permission to use one street as a play street. We were doing our own things at the same time as trying to steer this organisation.

(Dhelia:)

So, you had proposed certain ideas and you were elected onto this committee. At what point do you decide what the amenities under the Westway should finally be?

(Adam:)

As the Motorway Development Trust, we made a fairly detailed plan for possible uses of the space under the motorway. NKAT adapted this, but they didn't pursue any of the likeness of what we had proposed, it was dull – but it was something.

(Dhelia:)

How did that feel at the time?

(Adam:)

When we started, we knew that if we didn't fight, the land would become a car park. So we decided that if there was even just a marginal reason to fight, we would. Now, 50 years later, we are seeing some beginnings of a result.

(Dhelia:)

You prefaced this interview by telling me that speaking about this period can be demoralising for you. I can see why now. It must have been extremely frustrating, and you can sense that frustration even in some of the Motorway Development Trust archives. Particularly in some of the correspondence between yourself and the Council. It's also quite incredible what you achieved.

(Adam:)

It is. I'm just talking about the fun side of it compared to...

(Dhelia:)

Or you can talk about the not-fun side, if you prefer.

[Adam is prepared and has pulled out some of his archive onto his kitchen table.]

(Adam:)

50 years later, The Westway Trust has been found guilty of institutional racism and it’s no surprise.2 The Trust was against the neighbourhood almost from the beginning. 50 years of continual Tory council interference in the whole thing. Enough to exhaust you.

I'm just looking at some minutes of a meeting. It was a heavy bureaucracy approach. It was much easier for them to object to our proposals than to use their imagination. We really worked so hard on this. I was earning occasional photography work, but I spent the rest of my time doing this, writing thousands of letters to people. I was working nearly full-time on this for three years. After that, I couldn't take it anymore.

(Dhelia:)

When you started, did you realise there would be this level of bureaucracy?

(Adam:)

We knew what the Council was like, but the idea we had was a really good one. There was no treading on anyone else's feet as it was derelict land. It was entirely positive. Today the area is considered valuable, but back then, it was rubbish land to the Council and it was the best we could get. There was no chance of Kensington and Chelsea Council doing anything positive for North Kensington that we could see. They were busy laying flower beds in South Kensington.

(Dhelia:)

Which arguments do you think were most persuasive in winning your case?

(Adam:)

Well, there was a financial one. There was no money at the beginning and we were involved in gathering the seed funding for the project. We put forward our plan to City Parochial (known today as Trust for London), and we said, "If this Trust is set up, it will need money and the Council will starve this project. The thing will fall apart.” They said they would put aside £24,000 for two or three years’ time. It was a lot in today’s money. It was an extraordinary gesture on the charity’s part to earmark this money before the Trust was even established, without which the whole thing would have folded.

(Dhelia:)

To dream up the transformation of this disused land and to succeed in bringing the dream to life – it’s incredible, but you seem nonchalant about it.

(Adam:)

We somewhat succeeded.

(Dhelia:)

But imagine if they had gone ahead with a car park, it would've completely changed the dynamic of the area.

(Adam:)

At the time, it felt like nothing was impossible. In around 1968, we got the British Road Federation involved (which is the opposite of anything I would ever support). They gave us a whole bay at their convention show. Can you believe it? A group of rabble rousers from North Kensington. They paid for the 15 foot-long map of the motorway with our scheme written on it.

(Dhelia:)

What was their motivation behind supporting your proposal?

(Adam:)

At the time, no one had anything good to say about motorways, so we found allies in unlikely places. They thought the scheme was a wonderful idea.

(Dhelia:)

It seems like there was a real energy and cross-fertilisation between groups at the time. Do you think that contributed to your success?

(Adam:)

There was a strangely lively atmosphere at the time. The sixties were a real wake up time. We had to get rid of the fifties and that meant there was a possibility of trying something new. There was a gay liberation front starting at Notting Hill. Muhammad Ali visited Rhaune Laslett’s house. There was a feeling that things had to change – things were just too awful.

(Dhelia:)

So if you could go back, is there anything you would do differently?

(Adam:)

Machine guns… I’m joking. When we became the Motorway Development Trust, our number one rule was that we were going to have fun. We were really serious, but we also enjoyed each other’s company. We wanted change but the fun made it possible to keep going. You’ve got to have both. I mean, imagine, three years of full-time work for nothing.

(Dhelia:)

What do you think was the secret to your success?

(Adam:)

Our scheme was absolutely clean. There was no conflict of interest. We didn't change our plans because of the British Road Federation’s involvement. We were all working for free, the land was disused, it allowed us to think very freely.

(Dhelia:)

Was there ever a thought that the Motorway Development Trust would become the North Kensington Amenity Trust and you would manage the land yourselves?

(Adam:)

No. I think it was important that we didn’t have any ambition in that. If I would've been looking for a job, then it wouldn’t have worked out.

(Dhelia:)

Before we end, is this your handwriting by any chance? I found it scribbled on the back of a document in the archive. It says, “how to make the local authority do what you want”

[I show Adam the piece of paper.]

(Adam:)

Yes, it is.

(Dhelia:)

Do you want to read it?

(Adam:)

I don't know. What does it say?

(Dhelia:)

Do you want to guess what you said all those years ago? The question is… how do you get the local authority to do what you want?

(Adam:)

I think I would have said… You've got to get them from every angle, talk to your local vicar, to the newspapers, to your local councillors. Leave out nothing. Think of everything.

(Dhelia:)

Do you want to know what you wrote here? One of them is… Information Spy Network.

(Adam:)

Yeah. John was serious about it!

[I pass the paper for Adam to read.]

(Adam:)

“How to get the local authority to do what you want. Prepare plans, get local support and participation, do your research to find out what their plans are as well. Work on a Spy network. Publicity is important, it's useful. Confuse the opposition. Work on every level at the same time... That’s dynamite.”

(Dhelia:)

It's interesting because you used that same language earlier on without realising. You talked about working on every level, so that's clearly something that you've really carried forward.

(Adam:)

This note is lovely. Could you send me a picture of it?

1. Andrew Duncan, Taking on the Motorway: North Kensington Amenity Trust 21 Years (London: Kensington and Chelsea Community History Group, 1992).

2. Tutu Foundation UK was commissioned by Westway Trust in 2018 to conduct a comprehensive and fully independent review of Westway Trust's practices, both past and present, following allegations of institutional racism against the organisation by members of the community. The report found that the Trust has been and remains institutionally racist. The report's recommendations included a formal public apology, guarantees of non-repetition, and various reparatory justice measures, such as compensation.

“Get Us Out of This Hell”:

Life in the Shadow of the Westway

1 Robertson, S. (2007). Visions of urban mobility: the Westway, London, England. Cultural Geographies, 14(1), 74–91.

2 Duncan, A. (1992) Taking on the motorway: North Kensington Amenity Trust 21 Years. London: Kensington and Chelsea Community History Group.

The Westway Flyover was opened on July 28th 1970, by King Charles III. This two-and-a-half-mile long elevated highway suspended by giant concrete stilts was billed as the largest continuous concrete structure in the country. Although completed in 1970, the idea of developing the Westway as a major route in and out of London dates back to the 1930s.

Susan Robertson argues that in the face of Britain’s declining position on the world stage, “the Westway should be understood as forming part of a culturally specific desire to position Britain as progressive and technologically advanced” in a post-imperial context.1

At the time of the flyover’s construction, architects and planners did not consider London on par with cities like Paris or Brussels. Unlike those capitals—reshaped by figures like Haussmann and Leopold II — London had seen no comparable state-led transformation. The Westway was seen as a corrective.

Its sculptural, minimalist design contrasted sharply with Tower Bridge, completed in 1894 and long embraced as a symbol of imperial London. The Westway looked firmly to the future.

Praised as an engineering feat, it featured custom-built computer programs for structural calculations, along with electric heating on gradients and vibration-absorbing joints —signs of a project focused on engineering innovation.

But another narrative was brewing in West London: residents would complain that living amongst the construction was a “war time experience”.2

A roundabout on the Westway mid-way through construction, 1969. Source: PA Images / Alamy.

The site clearance for the flyover began in 1964. From 1966, four years of continuous construction work made the project London’s biggest ever road building scheme. However, what the marketing pamphlets failed to mention was that the Westway’s construction displaced roughly 492 families. The compulsory purchase and demolition of the homes to make space for the motorway also produced huge ecological destruction. It elevated 240,000 cubic yards of concrete and 21,000 tons of steel. Whole streets were chopped in half and residents living less than 30 feet from the development were effectively forced to live on a construction site. Like many urban motorways, it was built through a low income area with low car ownership figures. For residents, it was hard to see the benefits of the motorway that had carved their community in two.

Westway Flyover, A40. A crowd is gathered beside a journalist interviewing Michael Heseltine at the opening of the Westway Flyover. In the background, a protest banner draped over the adjacent houses reads “Get Us Out Of This Hell - Rehouse Us Now!”, 1970. Source: Historic England / Heritage Images / Alamy.

3 Vague, T. (2020) 'The Sound of the Westway', International Times.

4 Duncan, A. (1992), p. 15.

The Acklam Road residents’ representative George Clark protested to the Transport Minister, John Peyton: “I want to make a statement to the minister about the hell on earth in North Kensington. During the five years it has taken to construct this engineering marvel, the lives and social conditions of the residents of Acklam Road and Walmer Road have been made hell upon earth. For these people the new urban highway is a social disaster.” 3

At the opening of the flyover, Michael Heseltine also told the press: “There are two sides to this business. One is the exciting road building side but there is also the human side of this thing, and how huge roads like this affect people living alongside them. You cannot but have sympathy for these people.” 4

Mrs Terry looks up the Westway which is being built over her back garden in Oxford Gardens, North Kensington, 1969. Source: PA Images / Alamy.

5 ‘Inorganic and Organic Lead Compounds, IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 87’. Source: World Health Organisation.

The flyover was built before the Buchanan report of 1963, which called for new road schemes to take social and environmental factors into account. But by today’s standards, the motorway would have likely failed any modern impact assessment. No attempt was made to integrate the motorway with the area through which it passed. According to the literature from the time of the development, the disproportionate impacts on the local community and environment had hardly been considered by the architects responsible.

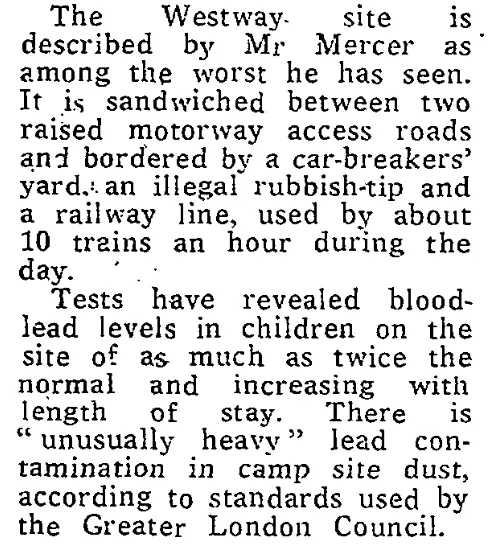

In the autumn of 1977, the long-planned Westway Nursery Centre was due to be opened underneath the Westway. However, the opening was delayed due to a number of setbacks, including worries that the lead levels in the air as a result of the heavy traffic would be dangerous to small children. Nonetheless, the nursery was eventually built despite serious health warnings. Within a few months of opening, 47,000 vehicles were passing overhead every day.

Four years later, in 1981, the Greater London Council (GLC) investigated blood-lead levels in children living in the ‘gypsy camp site’ underneath the Westway. They found children were living with ‘unusually heavy’ lead contamination (as much as twice the normal levels of lead in their blood). In 2004, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), part of the World Health Organization (WHO), published a report that classified lead as likely carcinogenic.5

“Health Challenge over Westway Gypsies’ Camp”, The Times (London), January 30, 1981.

Health challenge over Westway gypsies' camp.pdf (Click to open PDF)

“[The population] was about as far away from the middle class not-in-my-backyard sharp-elbowed, 2.5 children, middle-England as you could get. But that also made it a very vulnerable community as far as major works were concerned. It's no accident that these things happen in places of economic and social vulnerability,” says local artist and activist Toby Laurent Belson.

At face value, the Westway flyover was a success. A 40-minute journey would now take only 4 or 5 minutes, and the Westway was dubbed the 3-minute motorway. Yet locals were tormented by the construction and the repercussions of the motorway's development are still felt, even in the present day.

1 Susan Robertson, “Visions of Urban Mobility: The Westway, London, England,” Cultural Geographies 14, no. 1 (2007): 74–91.

2 Andrew Duncan, Takingonthe Motorway: North Kensington Amenity Trust 21 Years (London: Kensington and Chelsea Community History Group, 1992).

3 Tom Vague, “The Sound of the Westway,” International Times, 2020.

4 Duncan, Taking on the Motorway, 15.

5 World Health Organization, Inorganic and Organic Lead Compounds, IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, vol. 87 (Lyon: WHO, 2006)

Gravel Pits to Garden Squares:

The Transformation of Notting Dale

As late as the 19th century, pigs in Notting Dale outnumbered human residents three to one, sharing space in squalid and often inhumane conditions. In 1893, the Daily News described the area as the most “hopelessly degraded” part of London.1 Fast forward 100 years, and this corner of West London has become one of the UK's most expensive and fashionable neighbourhoods. So how did this dramatic transformation occur? In this interview, local historian Tom Vague offers context to the area’s complex transformation. Tom is writer and editor of the post-punk fanzine Vague. He has authored numerous publications on psychogeography and West London’s radical history.

(Dhelia:)

Let’s start with Notting Hill Gate. This project is entitled Gravel and Clay. So tell me about Notting Hill’s relationship to gravel in particular.

(Tom:)

Notting Hill Gate was known as the Kensington Gravel Pits. It was the gravel that made the area a resort of the rich and famous. As London became increasingly polluted, a spurious theory developed that it was healthier to live on a gravel layer than in a clay area. The aroma given off from the gravel carts was thought to be of particular medicinal benefit. The area’s fashionable appeal was confirmed when William III and Mary II moved to the area when London’s smog exacerbated his asthma.

Following the discovery of mineral water springs on the hill, purportedly containing Glauber or Epsom salts, the Kensington Wells House was built by John Wright, ‘a doctor of physic’, on the site of Campden Hill Square. Queen Anne’s son William was also lodged at Campden House and Lord Craven’s house by the Gravel Pits, in a futile attempt to prevent him dying young.

Kensington Gravel Pits, John Linnell, 1811–2. Source: Artepics / Alamy.

(Dhelia:)

So Notting Hill Gate was a popular rural enclave made famous for its gravel. Tell me about Notting Dale on the other hand.

(Tom:)

Notting Dale was known as the Potteries. The Norland brickfield was established by Stephen Bird. A bottle brick kiln still remains on what is now Walmer Road as a memorial to these industrious early days of suburban growth, when the soft local clay was fired into tiles, drainpipes and flower-pots.

(Dhelia:)

And the clay here was also used to make the bricks that helped London expand during the Industrial Revolution.

(Tom:)

Exactly. So there was Pottery Lane, but simultaneously, another slum area began to emerge after one Samuel Lake came into possession of some land at the north end of the Norlands estate. Samuel Lake was described as a chimney-sweep, scavenger and nightman, previously of Tottenham Court Road.2

In 1818, Samuel Lake moved out of London to continue his profession in the suburbs of London in Notting Dale. In 1819 Lake was joined by Stephens, a former bow-string maker, who became involved with a group of pigkeepers that were being evicted from Tyburn by the Bishop of London. Stephens invited the London pigkeepers to join his and Lake’s Norland Row colony in 1820, and it was then that the pigs moved into Notting Dale.

(Dhelia:)

When you’re saying this, it strikes me how young the area really is in terms of its urban history. I find it incredible that only 200 years ago our area was essentially a pig farm.

(Tom:)

It’s true. When the Potteries was first nicknamed ‘the Piggeries’, the pig population of 3,000 was said to be three times higher than the number of human inhabitants, with both species cohabiting in 250 hovels on eight acres.

(Dhelia:)

So in the 1820s, the pigs moved in and North Kensington was still entirely rural and Portobello Road a country path. But within the next 40 years the area would be part of London. How did that happen?

(Tom:)

An 1821 Act of Parliament enabled the Notting Hill building development to proceed. Then in 1823 the Commissioners of Sewers were presented with Thomas Allason’s plan for building on the Ladbroke estate.

In this plan, Ladbroke Grove was to be the axis of a mile in circumference of villas with a central garden around a church. As Pamela Taylor put it in her Old Ordinance Survey Maps, ‘this ambitious scheme was a failure, the first but by no means the last in the history of the development.’

(Dhelia:)

Why was it a failure?

(Tom:)

The Panic of the 1825 stock market crash happened and further building development was delayed for 20 years. But there were other issues too. Due to a gross over-provision for upper class housing, the first property developers - Jacob Connop and John Duncan - failed to let enough properties and were declared bankrupt in 1845.

(Dhelia:)

So there was this early intention to develop the area of Notting Hill into upper-middle class housing, but just around the corner, there’s the notorious piggeries in Notting Dale. How did that work?

(Tom:)

Well, it didn’t. Reverend Dr. Samuel Walker and others began to sink reputed millions into upper-middle class building development, disastrously close to the Potteries. Walker was responsible for causing hundreds of carcasses of houses to be built. If he had commenced his operations on the London side of the estate, no doubt the houses would have been sold and a fine investment made, but as he preferred building from Clarendon Road (where roads were not made) towards London, it meant the land was covered with unfinished houses, which continued in a ruinous condition for years.

(Dhelia:)

And so, how much of Thomas Allason’s plan was actualised before the bankruptcy?

(Tom:)

By the late 1840s the building of paired villas with communal gardens reached just over the hill to Elgin Crescent. And that was as far as the upper class Garden City was going to get.

(Dhelia:)

So now we have unfinished ‘carcasses’ of unoccupied upper-middle class housing near Notting Hill, how did Notting Dale fair in comparison?

(Tom:)

The potteries-piggeries evolved into a half rural, half urban rookery, without any building restrictions or sanitation measures.

(Dhelia:)

You mentioned a lack of sanitation measures and overcrowding, how was the health of residents?

(Tom:)

Not great, to say the least. Notting Dale has had some bad reviews over the years but the worst is still the 1849 preliminary report on the Potteries by Thomas Lovick, the assistant surveyor to the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers: “At all seasons [the piggeries] are in the most offensive and disgusting condition, emitting effluvia of the most nauseous character. The majority of the houses are of the most wretched class, many being mere hovels in a ruinous condition, and are generally densely populated”.3

The ditches fed into old clay pits, which became stagnant lagoons, the largest of which on the site of Avondale Park was known as ‘The Ocean’. The water in the wells was black and the paintwork on the shacks discoloured by the effect of the sulphuretted hydrogen gas. The smell of the pig fat and offal being boiled down in open vats set back the western building development for years.

(Dhelia:)

There’s a catch 22 here because pig-keeping was clearly contributing to the ill health of residents, but it was also the main source of income for the local population. Of course, there are no longer pigs in North Kensington, can you tell me what happened to those pig-keepers?

(Tom:)

Following the cholera epidemic of 1849, the first attempt to evict the pigs was made by the Metropolitan Board of Guardians. This prompted a local petition which revealed that 188 families, with 582 children, relied on pigs for their existence.

The Board of Guardians produced infectious disease figures showing an average life expectancy of 11 years and a child mortality rate of 87%, worse than Manchester and Liverpool. After there were middle class cholera fatalities on Crafton or Crafter Terrace, the state of the Kensington Potteries became Dickensian news.

There even became a ‘Save the Pigs’ type of campaign where the pig-keepers had representation from a lawyer. Their argument was that pig keepers were the first there and inherently had more rights. They argued it might be a health risk keeping pigs like this, but it's also their livelihood. There were even letters in the papers, including a pigkeeper’s plea to a journalist, “Pigs, sir? What harm can pigs do?” After ‘the Great Pig Case’ quarter sessions finally ruled the practice of pig-keeping a nuisance in a built up area, part of the Potteries was certified and demolished. The last of the pigs were evicted from Notting Dale in the late 1870s.

(Dhelia:)

That's really interesting to know that at almost each stage of development, there has been a tradition of counter protest. But also that those of us experiencing displacement in the borough are only the latest victims of a long tradition of social cleansing that started, believe it or not, with the pig-keepers and their pigs. So I want to ask, did things get ‘better’ from there?

(Tom:)

To give you an idea, in 1893, the surrounding Notting Dale slum area was described in the Daily News as a ‘West End Avernus’, after Lake Avernus, the entrance to hell in classical mythology. In fact, a London City Mission report in 1891 led to more bad press in which the area was called ‘a disgrace to Christianity and civilisation.’

(Dhelia:)

It's a conversation for another day but I also find this really interesting, because of course, missionaries are so much part of the earlier story of Notting Dale. When we talked about Samuel Walker, for example, he was a Reverend but he was also instrumental to much of the early property development in the area. But going back to the timeline for a moment, what happened to those homes that were originally built for the prospective upper-middle class residents-to-be?

(Tom:)

In the 1880s, the original upper class residents of the squares, such as Powis and Colville, failed to renew their leases, and by then some houses were already subdivided into flats and maisonettes. Especially in the case of Bangor and Crescent, in Florence Gladstone’s words, ‘whole streets were not inhabited by the class of people for whom they were designed.’4

(Dhelia:)

So moving forward a little. By the 1860s and 70s, the area had almost fully transitioned away from pig-keeping and brickmaking. Can you tell me more about this transition?

(Tom:)

With the decline of pig-keeping and brickmaking, the next chief local industry was laundry work. As the profession grew from small in-house hand laundering establishments to industrialised factory-size steam laundries, Notting Dale and Kensal New Town became known as ‘Laundry Land’. People in Notting Dale would hand-wash the clothes of people living in Notting Hill. After that, factory, railway and omnibus work replaced pig-keeping, brickmaking, navvying and hand-laundering as the main forms of local employment.

(Dhelia:)

Moving chronologically then, that takes us to the turn of the century. What does the area look like at this point?

(Tom:)

In many ways, not much had changed. When Kensington was made a royal borough in 1901 by Edward VII, part of it was described as a ‘criminal and irreclaimable area’ inhabited by ‘vicious, semi-criminal people.’ On the class colour-coded map of Charles Booth’s Life and Labour of the People of London survey, the Notting Dale ‘Special Area’ streets (Bangor, Crescent, Kenley and St Katherine’s) stand out in lowest class/criminal black with a very poor blue buffer zone, of Pottery Lane, Portland Road, the Potteries and Talbot Grove, blocking off the poor ghetto area from the well-to-do orange and wealthy yellow hill. As the London County Council found little difference between the child mortality rates of the new Notting Dale slum and the old Potteries, it was estimated that 67% of the population of the Special Area had just enough income for ‘mere physical efficiency.’

Charles Booth’s Life and Labour of the People of London, 1901. The Notting Dale ‘Special Area’ streets (Bangor, Crescent, Kenley and St Katherine’s) stand out as “lowest class” in the map’s key. Well-to-do Notting Hill and Campden Hill are in yellow, which represents “wealthy” in the map’s key. Source: Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy.

(Dhelia:)

Surprise, surprise, the clearance of the pigs and the building of upper middle class housing did not erase the poverty. So, to end almost back at the start, we’ve talked about the first permanent residents of Notting Dale as the pigkeepers and their eventual displacement from the land, but of course, before the permanent residents, there were visitors who lived in Notting Dale on a seasonal basis long before the pigs arrived. Of course, there is still a caravan site under the Westway, but they’re almost erased from the story of the area. Where does the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller community fit into this story?

(Tom:)

From the start, the people of Notting Dale were people being displaced from slum areas of Central London and from other places as well. The main Notting Dale gypsy families were the Hearns, Kimbers and Wests, but their presence has diminished. In the final stages of urbanisation, the Notting Dale gypsies were integrated into the community by a combination of do-gooding and health restrictions. 50 gypsy families settled in permanent accommodation and took an oath, signing a missionary pledge to abstain from drunkenness, swearing and fortune-telling. They also sold their horses, stopped speaking Romany and acquired hawkers’ licences.

(Dhelia:)

Tom, thank you so much for your scholarship and all your work documenting our area. It’s so invaluable.

1. Renwick, D. and Shilliam, R. (2022) Squalor. Newcastle upon Tyne: Agenda Publishing.

2. A nightman is a sewage collector or cesspit cleaner.

3. A preliminary report by Mr Thomas Lovick, Assistant Surveyor, on the "Potteries," Kensington: in pursuance of the order of the Works' Committee of 21st February, 1849. March 12th, 1849. Metropolitan Commission of Sewers. Source: Wellcome Collection.

4. Bangor Street no longer exists but would have been on the site of the present day Henry Dickens estate.

Introduction:

Gravel and Clay is a 10-chapter printed publication with contributions from Adam Ritchie, Edward Daffarn, Emma Dent Coad and Tom Vague. This online selection features 4 of the 10 chapters, including the contributions from Adam Ritchie and Tom Vague.

Kensington and Chelsea is one of the most unequal boroughs in Britain. In Golborne ward, more than two-thirds of residents experience some form of deprivation, while in parts of South Kensington almost half of households own their homes outright. Life expectancy, housing conditions and health outcomes all vary dramatically within just a few miles.

This project uses the borough’s soil as a way to think about these contrasts. Its title comes from a 1920 geological survey that mapped Kensington’s uneven soil composition: gravel in the south, clay in the north.

In the nineteenth century, Notting Hill Gate was more commonly known as the Kensington Gravel Pits. Its gravel was exported around the world and praised for its health-giving properties.

Notting Dale, by contrast — later home to Grenfell Tower — was built on clay-heavy brickearth. With its poor drainage and risk of contaminated water, clay land was never a favourable choice for developers, and the area remained underdeveloped except for a few struggling farms. Meanwhile, the Kensington Gravel Pits became a health resort for London’s gentry seeking respite from the city.

In this collection of essays and interviews, Gravel and Clay takes Notting Hill’s celebrated gravel and North Kensington’s stubborn clay as a motif and point of departure to reflect on the borough’s present-day inequalities.

Geological Survey of England and Wales, Edition of 1920