Blue Skies: Jillian Mayer & Adelaide Bannerman - You’ll Be Okay

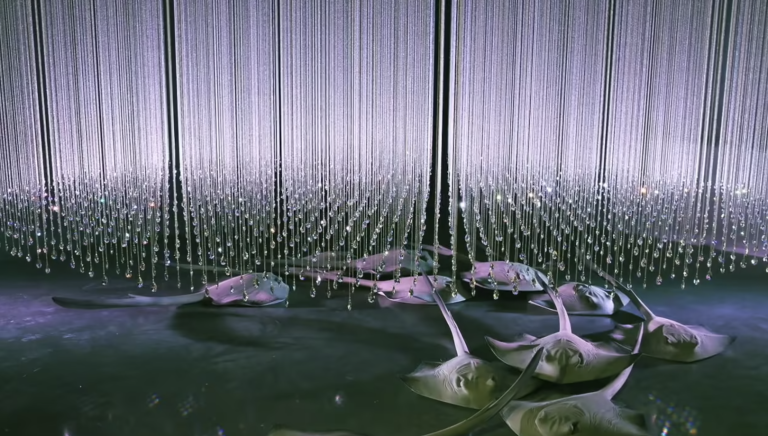

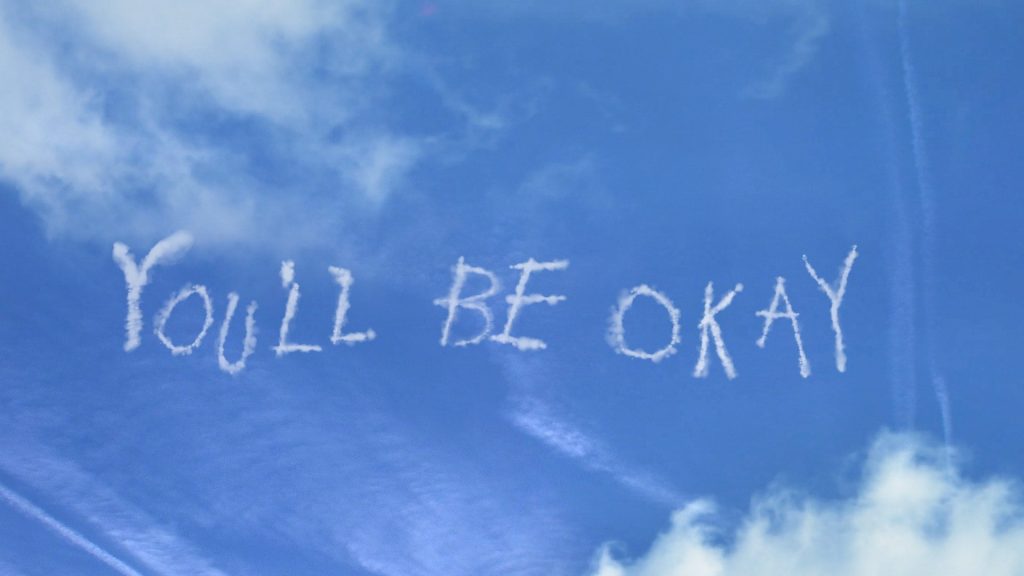

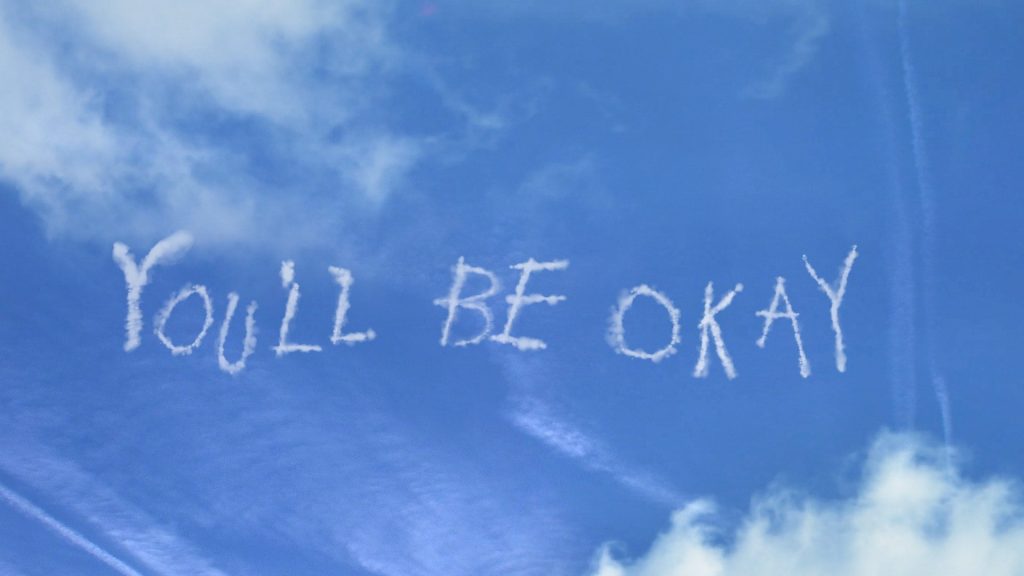

The lead-image for the Blue Skies conversation series is a still from artist Jillian Mayer’s 2014 video You’ll Be Okay, encountered at Prospect 4: The Lotus In Spite of The Swamp, New Orleans 2017/18. ICF approached Mayer during May 2020 to find out how she was, about her recent activity and to capture her reflection on the work itself, reviewing its original intent, and it’s reading in the moment of the pandemic.

“…What a humanly thing to do to write a message across the sky, right? Like kind of an insane idea, but we figured it out.” Jillian Mayer

Adelaide Bannerman: Hi, Jillian. Nice to meet you.

Jillian Mayer: Hello, thanks for having me digitally.

Adelaide Bannerman: You’re very welcome. It’s a real pleasure to be speaking with you as the artist of our leading image for Blue Skies, which is to be a new conversation series that we’re rolling out over the next few months. I just wanted to introduce you to our audiences and thought maybe first to ask you how you’ve been in the last few months?

Jillian Mayer: So I did have Corona COVID-19 so I lost about a month to being confused and sleepy. I slept a lot, and was a bit foggy. But I’ve since tested negative a couple of times and I also had an antibodies test. But while I was ill, I made so much work, so many things in my backyard studio, but I don’t really remember making all of them because I was so exhausted and confused. Now, I’m doing okay, I’m doing fine. I have no sense of smell, it’s been like three months since I’ve smelled a thing, which is just a strange new situation. But I’m still very grateful that I never was in a situation where I thought that something was going very direly wrong. Also, I’m very grateful that it’s just that I have no smell rather than being stuck on something that maybe smells bad. Could you imagine if just everything smelt bad? So for me, I’m just grateful. I’m missing some data, essentially, but I was never in a serious situation of harm or extreme illness. I feel very grateful that I have a place to sleep and to rest. I don’t want to say check your privilege to anyone, but be grateful for whatever privilege or access you have. During my time with the pandemic, I made a lot of things, people in my family were detained, many of my projects collapsed, my dog died… ultimately, I think this was a reset for a lot of people. I know we are all thinking differently about how to move forward, I hope people are – so that gives me hope. I’m quite optimistic, so I try and look at the good things that could come out of this situation, even if it’s frightening and uncomfortable. I think of myself, and my art practice as very solution-oriented.

Adelaide Bannerman: We’re experiencing that kind of reflection on so many different levels. I mean, it’s the prime moment for that, you kind of hope that people will be confident enough to look this in the eye, and not deny or think that there’s some kind of normal that they’re returning to, and that they’ll take confidence in a landscape that will change. I guess it’s how it changes and what the implications are really. And that’s kind of behind the Blue Skies series really for us. I mean, as an organisation, we’re asking our own questions about how we want to do things differently or how we respond to audiences, participants and collaborators that we’ve been working with over the last number of years, but I guess it’s about also trying to collect a poly vocal response that will try to speak things into existence, speak the changes that you want to see. So that’s what we’re kind of hoping for ourselves and trying to invite people along to actually see what we can action collectively. It’s a heavy moment.

Jillian Mayer: Yes, and it’s interesting because as someone who’s grown up with the media and advertising offering every opportunity for someone to reach an avid viewer, it’s this thing where I’m wondering if things are really bad right now or not so bad when compared historically or if we merely have more global connectivity, so we’re able to be more conscious of injustices that occur? So when we ask questions like, are we going to go back to anything? Are we going to like what this new normal is? Was the old normal so great? Or was it pretty alright? Does that depend on who you are, where you were born and what you look like?

I often wonder about the concept of world peace and if the world could ever be at peace – all at once? And what would have to conceptually and practically change for that? And… is that possible? These are large questions that when you ask them aloud, sound basic and elementary, but it’s still something that you hope could be resolved in some sense, where not everyone was suffering or felt they were suffering. I don’t know. Is utopianism too far away? And also, is it even possible for people to understand utopianism, if they had a chance to have it for themselves? Or would they always want more? I don’t know.

Adelaide Bannerman: For some people that is a luxury, you know, just even to dream that or even try to see what that could be.

Jillian Mayer: One person’s needs and expectations are so much more remedial than another. So would sacrifice have to come with utopianism for all, and then is it actually utopianism for some? I don’t know. Some people also believe that their utopianism exists in their next life, that this current state is the pain and suffering.

Adelaide Bannerman: Closer to home, and tangible in terms of the last few months your last solo show, which was at the Bemis Centre for Contemporary Arts, Nebraska. It’s been described as a commentary on environmental and infrastructural collapse. And so I was just wondering if you’d like to talk about that?

Jillian Mayer: Sure. So in February 2018, this show titled Time Share, initially opened up the UB Galleries, University of Buffalo, New York, and in November 2019, opened at Bemis Centre for Contemporary Arts in Nebraska, and it’s to be travel again to South Carolina. Time Share was a consideration of environmental situations, the institutional art space, privilege and accessibility in terms of access. And what I mean by that is, we have all known some body of water or some place where you wouldn’t eat food from or wouldn’t go swimming, in that is just too dirty, and we’re kind of okay with that. We accept that as a status of that environment.

So I imagined a future when all of our exterior environments are like that, where perhaps we be in a world where we’ll have to stay inside indefinitely. And in the way that we often go to art institutions to see moments of history and movements that have been archived in some type of canon, whether it’s a national history museum or just viewing art from other time periods, perhaps nature will be handled the same way and will have this artificial recreation that’s to imply the natural experience.

The natural experience I was most influenced by for the show was the sculpture garden or the garden, which is ultimately a curated environmental space. So it’s already playing on itself. But we come to accept it – regardless of the fact that it contains plants and animals that shouldn’t be located together in one amount of acreage – they’re there, we go and we like it. We adapt. We’re in the city and we would like to go outside, so we say “let’s go to this garden,” which is all manicured and human adjusted; human affected. Time Share is comprised of installations and different works that address how nature looks when reconstructed from up-cycled materials that are not biodegradable (such as foam and fibreglass).

The works invite the viewer to sit and spend time on/in them – to allow the viewer to feel as if they’re outside, but not in such a kitschy way that it feels like a themed restaurant or ride. My intention was to keep it very sculptural. But the underlying idea was of nature being able to be interpreted as an aesthetic force for contemporary sculpture. You could interact with many of the works, many of the installations. They sort of work as functional furniture or different benches. There’s a fountain that had serotonin in it. I wanted people to be able to run their hands through this water with serotonin and splash it on their face. Serotonin and dopamine rise in a person when they go out and experience authentic nature. As an artist, I had the ability to mediate this experience and replicate it – so I took it. There were a lot of living plants that were purchased for this show.

There’s this very popular meme of a little cartoon dog that’s on fire. Basically, it’s the meme of the dog where everything around him is on fire, and he’s just saying, “This is fine.” And it’s a line that women tend to say on the whole, like, “I’m fine, I’m fine.” Or “I’m sorry,” you know, for things that aren’t really our fault. So I did make a melted metal piece that just says ‘I am fine’.

Although I mentioned that much of my work takes place in a solution oriented manner hinged on optimism, so much of it is about adaptation and communication. And when one deals with a problem that’s so much bigger than oneself, or a problem that’s so large that it feels so much bigger than something that we could retract and actually make amends to, what do you do with that feeling?

Humans adapt, we generally override it or just declare that the water is ‘too dirty.’ So it’s dealing with a lot of these feelings. I made that show mainly in South Florida, where I live – in Miami. And it’s a very tropical place; the colour palette of the show reflects my outdoor studio. For Time Share, the pieces came from Miami and it feels quite organic for me to see what is essentially an installation of my outdoor surroundings travel around to these locations that somehow always seem to exhibit me in the most cold months. I think this particular show offers refuge or respite from some of the locations that have wanted to show it.

Adelaide Bannerman: Going back to talking about using your work as a tool of communication, and thinking about what you wrote large in the sky for your work, “You’ll be okay“. Can you recollect what you were responding to that time when you were making the work?

Jillian Mayer: Lately, people have assumed this message simply to be a very optimistic mimetic bumper sticker, but for me it was coming from a more complicated transmission of cross-communication.

For the ‘You’ll Be Okay‘ text, I simultaneously intended to present both forward and mirror versions, so that the text would appear backwards to the viewer, if you were the viewer. And what a humanly thing to do – to write a message across the sky, right? It’s kind of an insane idea, but we figured it out. And then by putting a message that says ‘you’ll be ok,’ that speaks to someone below who’s reading it, it’s an open gesture because ultimately, it reassured the reader but not without confusion. Who is this for? Who wrote it? Is this written from an outer world to us?

That is the reason why I wanted to simultaneously present it backwards – to position it as the possibility of correspondence from a different world, which then allows a viewer to wonder -Who might they be? Are they writing it for themselves? Or are they writing it to us? Or if we wrote it for ourselves, is someone else seeing it backwards?

I am interested in the planted notion for exchange. Every four minutes, the message ‘you’ll be okay’ loops and fades away. It is to reflect that we are all in a system, and even if the reassuring message fades away, it reboots. It’s kind of this artificially digitally enhanced pat on the head.

Adelaide Bannerman: But it was a beautiful moment. I think I stood in there for a few cycles of it, because it was just such a simple kind of gesture. But yes. I mean, the connotations and for who and how it speaks is innumerable I guess it depends on how you’re feeling in that moment when you walk into it as well.

Jillian Mayer: Yes, I remember telling one of my art mentors that I felt my practice leaning towards text-based work. And I remember them saying to me, “you know, the problem with text art is that it’s just so literal.” I thought so much about that, and ultimately concluded that the way to avoid that pit hole is that I would need the text to skew more poetic, more abstracted. Employing different presentational aspects or cinematic elements, editing, lighting, everything – it could be less literal, but it could also resonate with the people who needed to find it when they did.

Adelaide Bannerman: It was certainly very powerful, very memorable as well, so it’s really nice to draw back to it again and have a small exchange, you around it, thank you very much Jillian.

Jillian Mayer: Thanks for talking to me about it.

For more information about the works discussed in the conversation visit the artist’s website.

People:

Project:

The lead-image for the Blue Skies conversation series is a still from artist Jillian Mayer’s 2014 video You’ll Be Okay, encountered at Prospect 4: The Lotus In Spite of The Swamp, New Orleans 2017/18. ICF approached Mayer during May 2020 to find out how she was, about her recent activity and to capture her reflection on the work itself, reviewing its original intent, and it’s reading in the moment of the pandemic.

“…What a humanly thing to do to write a message across the sky, right? Like kind of an insane idea, but we figured it out.” Jillian Mayer

Adelaide Bannerman: Hi, Jillian. Nice to meet you.

Jillian Mayer: Hello, thanks for having me digitally.

Adelaide Bannerman: You’re very welcome. It’s a real pleasure to be speaking with you as the artist of our leading image for Blue Skies, which is to be a new conversation series that we’re rolling out over the next few months. I just wanted to introduce you to our audiences and thought maybe first to ask you how you’ve been in the last few months?

Jillian Mayer: So I did have Corona COVID-19 so I lost about a month to being confused and sleepy. I slept a lot, and was a bit foggy. But I’ve since tested negative a couple of times and I also had an antibodies test. But while I was ill, I made so much work, so many things in my backyard studio, but I don’t really remember making all of them because I was so exhausted and confused. Now, I’m doing okay, I’m doing fine. I have no sense of smell, it’s been like three months since I’ve smelled a thing, which is just a strange new situation. But I’m still very grateful that I never was in a situation where I thought that something was going very direly wrong. Also, I’m very grateful that it’s just that I have no smell rather than being stuck on something that maybe smells bad. Could you imagine if just everything smelt bad? So for me, I’m just grateful. I’m missing some data, essentially, but I was never in a serious situation of harm or extreme illness. I feel very grateful that I have a place to sleep and to rest. I don’t want to say check your privilege to anyone, but be grateful for whatever privilege or access you have. During my time with the pandemic, I made a lot of things, people in my family were detained, many of my projects collapsed, my dog died… ultimately, I think this was a reset for a lot of people. I know we are all thinking differently about how to move forward, I hope people are – so that gives me hope. I’m quite optimistic, so I try and look at the good things that could come out of this situation, even if it’s frightening and uncomfortable. I think of myself, and my art practice as very solution-oriented.

Adelaide Bannerman: We’re experiencing that kind of reflection on so many different levels. I mean, it’s the prime moment for that, you kind of hope that people will be confident enough to look this in the eye, and not deny or think that there’s some kind of normal that they’re returning to, and that they’ll take confidence in a landscape that will change. I guess it’s how it changes and what the implications are really. And that’s kind of behind the Blue Skies series really for us. I mean, as an organisation, we’re asking our own questions about how we want to do things differently or how we respond to audiences, participants and collaborators that we’ve been working with over the last number of years, but I guess it’s about also trying to collect a poly vocal response that will try to speak things into existence, speak the changes that you want to see. So that’s what we’re kind of hoping for ourselves and trying to invite people along to actually see what we can action collectively. It’s a heavy moment.

Jillian Mayer: Yes, and it’s interesting because as someone who’s grown up with the media and advertising offering every opportunity for someone to reach an avid viewer, it’s this thing where I’m wondering if things are really bad right now or not so bad when compared historically or if we merely have more global connectivity, so we’re able to be more conscious of injustices that occur? So when we ask questions like, are we going to go back to anything? Are we going to like what this new normal is? Was the old normal so great? Or was it pretty alright? Does that depend on who you are, where you were born and what you look like?

I often wonder about the concept of world peace and if the world could ever be at peace – all at once? And what would have to conceptually and practically change for that? And… is that possible? These are large questions that when you ask them aloud, sound basic and elementary, but it’s still something that you hope could be resolved in some sense, where not everyone was suffering or felt they were suffering. I don’t know. Is utopianism too far away? And also, is it even possible for people to understand utopianism, if they had a chance to have it for themselves? Or would they always want more? I don’t know.

Adelaide Bannerman: For some people that is a luxury, you know, just even to dream that or even try to see what that could be.

Jillian Mayer: One person’s needs and expectations are so much more remedial than another. So would sacrifice have to come with utopianism for all, and then is it actually utopianism for some? I don’t know. Some people also believe that their utopianism exists in their next life, that this current state is the pain and suffering.

Adelaide Bannerman: Closer to home, and tangible in terms of the last few months your last solo show, which was at the Bemis Centre for Contemporary Arts, Nebraska. It’s been described as a commentary on environmental and infrastructural collapse. And so I was just wondering if you’d like to talk about that?

Jillian Mayer: Sure. So in February 2018, this show titled Time Share, initially opened up the UB Galleries, University of Buffalo, New York, and in November 2019, opened at Bemis Centre for Contemporary Arts in Nebraska, and it’s to be travel again to South Carolina. Time Share was a consideration of environmental situations, the institutional art space, privilege and accessibility in terms of access. And what I mean by that is, we have all known some body of water or some place where you wouldn’t eat food from or wouldn’t go swimming, in that is just too dirty, and we’re kind of okay with that. We accept that as a status of that environment.

So I imagined a future when all of our exterior environments are like that, where perhaps we be in a world where we’ll have to stay inside indefinitely. And in the way that we often go to art institutions to see moments of history and movements that have been archived in some type of canon, whether it’s a national history museum or just viewing art from other time periods, perhaps nature will be handled the same way and will have this artificial recreation that’s to imply the natural experience.

The natural experience I was most influenced by for the show was the sculpture garden or the garden, which is ultimately a curated environmental space. So it’s already playing on itself. But we come to accept it – regardless of the fact that it contains plants and animals that shouldn’t be located together in one amount of acreage – they’re there, we go and we like it. We adapt. We’re in the city and we would like to go outside, so we say “let’s go to this garden,” which is all manicured and human adjusted; human affected. Time Share is comprised of installations and different works that address how nature looks when reconstructed from up-cycled materials that are not biodegradable (such as foam and fibreglass).

The works invite the viewer to sit and spend time on/in them – to allow the viewer to feel as if they’re outside, but not in such a kitschy way that it feels like a themed restaurant or ride. My intention was to keep it very sculptural. But the underlying idea was of nature being able to be interpreted as an aesthetic force for contemporary sculpture. You could interact with many of the works, many of the installations. They sort of work as functional furniture or different benches. There’s a fountain that had serotonin in it. I wanted people to be able to run their hands through this water with serotonin and splash it on their face. Serotonin and dopamine rise in a person when they go out and experience authentic nature. As an artist, I had the ability to mediate this experience and replicate it – so I took it. There were a lot of living plants that were purchased for this show.

There’s this very popular meme of a little cartoon dog that’s on fire. Basically, it’s the meme of the dog where everything around him is on fire, and he’s just saying, “This is fine.” And it’s a line that women tend to say on the whole, like, “I’m fine, I’m fine.” Or “I’m sorry,” you know, for things that aren’t really our fault. So I did make a melted metal piece that just says ‘I am fine’.

Although I mentioned that much of my work takes place in a solution oriented manner hinged on optimism, so much of it is about adaptation and communication. And when one deals with a problem that’s so much bigger than oneself, or a problem that’s so large that it feels so much bigger than something that we could retract and actually make amends to, what do you do with that feeling?

Humans adapt, we generally override it or just declare that the water is ‘too dirty.’ So it’s dealing with a lot of these feelings. I made that show mainly in South Florida, where I live – in Miami. And it’s a very tropical place; the colour palette of the show reflects my outdoor studio. For Time Share, the pieces came from Miami and it feels quite organic for me to see what is essentially an installation of my outdoor surroundings travel around to these locations that somehow always seem to exhibit me in the most cold months. I think this particular show offers refuge or respite from some of the locations that have wanted to show it.

Adelaide Bannerman: Going back to talking about using your work as a tool of communication, and thinking about what you wrote large in the sky for your work, “You’ll be okay“. Can you recollect what you were responding to that time when you were making the work?

Jillian Mayer: Lately, people have assumed this message simply to be a very optimistic mimetic bumper sticker, but for me it was coming from a more complicated transmission of cross-communication.

For the ‘You’ll Be Okay‘ text, I simultaneously intended to present both forward and mirror versions, so that the text would appear backwards to the viewer, if you were the viewer. And what a humanly thing to do – to write a message across the sky, right? It’s kind of an insane idea, but we figured it out. And then by putting a message that says ‘you’ll be ok,’ that speaks to someone below who’s reading it, it’s an open gesture because ultimately, it reassured the reader but not without confusion. Who is this for? Who wrote it? Is this written from an outer world to us?

That is the reason why I wanted to simultaneously present it backwards – to position it as the possibility of correspondence from a different world, which then allows a viewer to wonder -Who might they be? Are they writing it for themselves? Or are they writing it to us? Or if we wrote it for ourselves, is someone else seeing it backwards?

I am interested in the planted notion for exchange. Every four minutes, the message ‘you’ll be okay’ loops and fades away. It is to reflect that we are all in a system, and even if the reassuring message fades away, it reboots. It’s kind of this artificially digitally enhanced pat on the head.

Adelaide Bannerman: But it was a beautiful moment. I think I stood in there for a few cycles of it, because it was just such a simple kind of gesture. But yes. I mean, the connotations and for who and how it speaks is innumerable I guess it depends on how you’re feeling in that moment when you walk into it as well.

Jillian Mayer: Yes, I remember telling one of my art mentors that I felt my practice leaning towards text-based work. And I remember them saying to me, “you know, the problem with text art is that it’s just so literal.” I thought so much about that, and ultimately concluded that the way to avoid that pit hole is that I would need the text to skew more poetic, more abstracted. Employing different presentational aspects or cinematic elements, editing, lighting, everything – it could be less literal, but it could also resonate with the people who needed to find it when they did.

Adelaide Bannerman: It was certainly very powerful, very memorable as well, so it’s really nice to draw back to it again and have a small exchange, you around it, thank you very much Jillian.

Jillian Mayer: Thanks for talking to me about it.

For more information about the works discussed in the conversation visit the artist’s website.

Dates:

3 Aug 2020

Location:

Online

Tags

Explore Further

Explore Further

Kashif Nadim Chaudry: Diaspora Pavilion 2 Artist in Conversation (Transcript)