Sensational Bodies – An Interview with Ada M. Patterson

7 Sep 2018

People:

Location:

Jerwood Place, London

People:

Location:

Jerwood Place, London

ICF Head of Programmes Jessica Taylor interviewed artist Ada M. Patterson about their practice and the work they presented in the project Sensational Bodies, a performance and film programme curated by Taylor and Adelaide Bannerman for the 2018 Jerwood Staging Series

Sensational Bodies presented the work of two artists who consider expanded ways of seeing and speaking beyond the historicised or everyday through performance. In their practice Ada M. Patterson explores strategies of resistance to particular neo-colonial structures, working to subvert perceptions and deconstruct tropes associated with the post-colonial Caribbean. Interested in the fragility and vulnerability of human existence, Rubiane Maia examines the synergies and relationships between bodies, objects and nature.

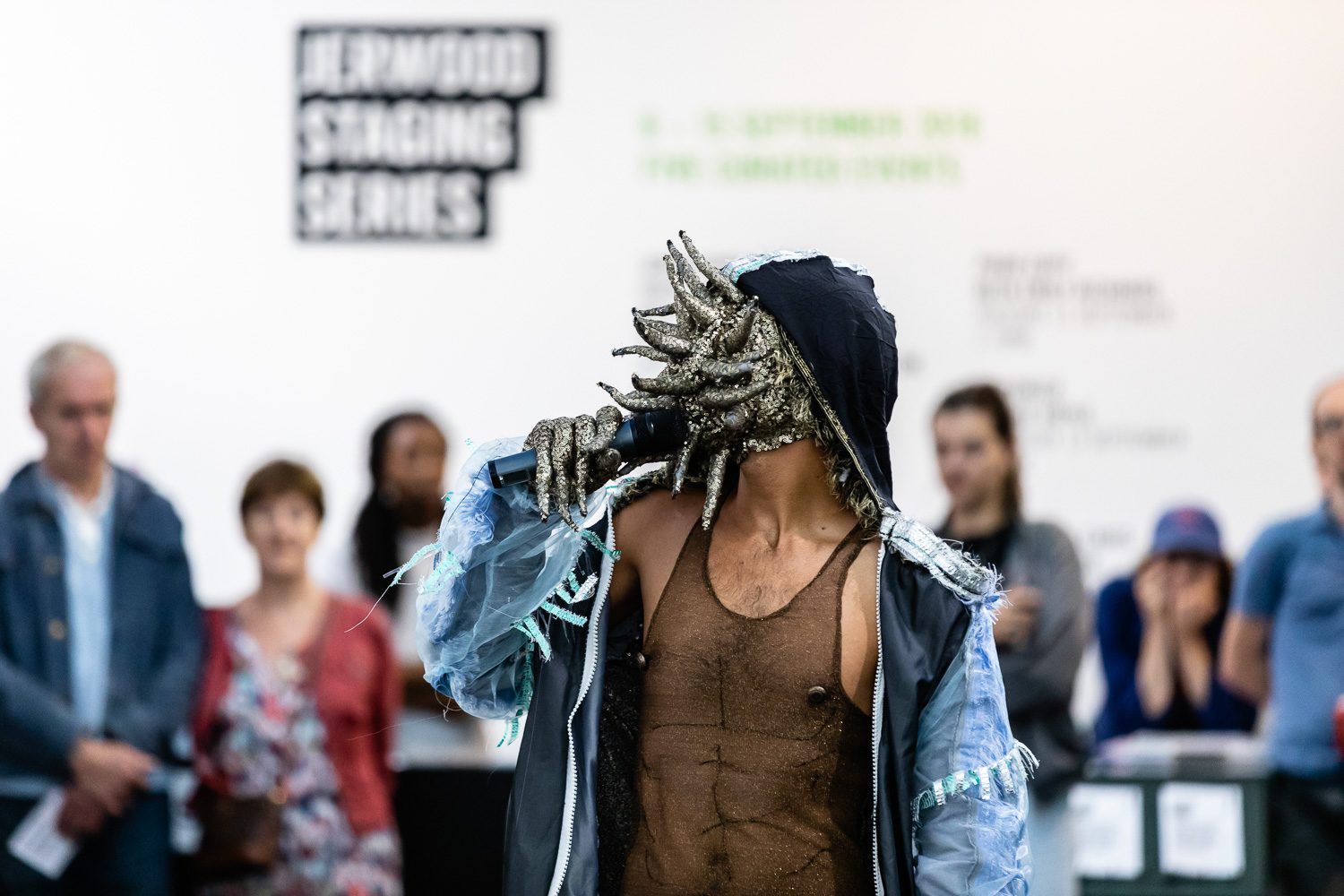

Responding to particular constructions of masculinity, Ada M. Patterson presented a new performance for Sensational Bodies entitled Bikkel. Its namesake referring to the Dutch word for a man with an inauthentic strength or toughness, Bikkel adopts and re-imagines the motif of the sea urchin, depicting the spiked marine animal not as hard, brittle and defensive but as elastic and porous, with the capacity to be held and squeezed. Patterson’s approach to masculinity in this formation of Bikkel is inspired by Audre Lorde’s turn to love and softness as a means of survival and a tool of resistance against social expectations of gender.

Ada M. Patterson, Bikkel (2018) Sensational Bodies, Jerwood Staging Series (2018). Image by Hydar Dewachi

Jessica Taylor: Can you speak a bit about the motivations behind the character of Bikkel?

Ada M. Patterson: Only for the past year have I been opened to the writings and thoughts of Audre Lorde. Lorde’s criticism of hardness and welcoming of softness, as these notions relate to opposing characteristics of masculinity and femininity respectively, really pushed me to reconsider certain approaches I have previously undertaken in my work which, for me, are now questionable and thus subject to scrutiny, reflection and revision. It led me to consider my own masculinity and the various social sources of masculinity that may have unconsciously shaped me between my upbringing in Barbados and my time of study and living in both London and Rotterdam. There is also the consideration that some of these social conditionings have failed me or that I’ve failed them by not meeting certain standards of masculinity and manhood. Bikkel comes from this place of expectation of masculinity and failing to perform certain expectations, alongside the conflict that comes from such conditions, and how this may or may not be reconciled.

J: There are several visual and behavioural elements that you bring together to form Bikkel – through costume, gesture, movement and script. Can you elaborate a bit on how those elements came together?

A: In his initial conceptualization, Bikkel stems from the types of fashion I’ve noticed in men of both London and Rotterdam. His silhouette borrows from tracksuits, bomber jackets and hoodies. There is a rich culture encoded in how these types of fashion and the brands they come in appeal to particular values and merits of masculinity, male prosperity, power and potency. Uninterested in criticizing it, what I appreciate most about it is its ideological conflict; that such soft and comfy clothes are also athletic wear that suggest physical or muscular exertion but also metaphorically refer to a particular masculine ideal. In essence, they are clothes that signify a male hardness or power but are soft and comforting in their physical nature. The use of script is important to me as it allows a moment for the character to live through speaking, through confession and memoir. It’s usually a conflicted reflection or explanation, which isn’t always too reliable or coherent as a piece of information. The script, the spoken word, the voice – these are tools to allow the character to reflect on itself and the usually twisted and unconsented circumstances of its coming into being. It’s like a self-obituary or exorcism or libation, whereby the character is confronted with the reflection of itself, trying to find rest in reconciliation in the difficulty of its reasoning, its being, its ideological heritage and inheritance.

J: How does the motif of the sea urchin – which you have incorporated into the character of Bikkel – function as a means of talking about notions of masculinity?

A: I have used the sea urchin as a tropical image of a beauty that is seductive and therefore dangerous; beautiful to look at, harmful to the touch. In its anatomy, it is a disinterested creature, facing the ground in contemplation, raising a host of thorns to protect itself from external forces. I have used it as an image resisting touristic and consumptive desires against my body, an image that defies a passive paradisiacal nature, a militarized paradise, a paradise in resistance. Bikkel’s spiked urchin face hopes to draw on this image of all the face’s pores, mouths and orifices closing and raising spikes – to suggest a state of being inaccessible, unapproachable, distanced, unable to speak or be spoken to, brittle, hard, closed, non-relational, which I think are all qualities of toxic forms of masculinity.

J: Bikkel is responsive to your use of the sea urchin in previous work as rigid and unimpressionable, how is the shift to a porous and more open way of addressing ideas of masculinity evident in the Bikkel performance informed by the writings of Audre Lorde?

A: In the course of the script, Bikkel remarks on the softening of his spikes. It’s uncertain whether he will open fully but his brittle bony spikes melt to sponge and this porosity suggests a newfound openness. Reflecting on my previous work with sea urchin imagery, I fear the work is too tense and brittle, on the verge of shatter, in constantly resisting, forming itself in resistance. The softening, the loosening, contraction and lax in Bikkel’s spikes is a return towards a relational posture, materiality and approach. Bikkel’s mask is a soft stuffed mask, capable of being squeezed and holding its form in reflex. It’s this kind of reflex which allows for an indestructible vulnerability. Audre Lorde has indeed opened me to the ideas of finding power in softness and vulnerability, but it’s not about being without guard. We can still protect ourselves while actualizing more relational behaviors in ourselves.

J: You reference a variation of a line from her essay ‘Man Child’ at the very end of the Bikkel script – “If I cannot love and resist at the same time, I will probably not survive.” We’ve spoken above about love or softening as a form of survival –Do you think it is fair to say that enacting the relational behaviours that you mention above, both within ourselves and with others, can be a form of resistance to the generalizing or reductive forces at work in society in regards to gender and beyond?

A: Although Lorde, in that essay, is specifically speaking about her son, that excerpt refers to both her children. In surrendering my confidence as a “grown man,” it allows me the space to think of myself as a boy who’s still learning about myself and trying to find healthier ways of coming into myself and coming into the world. It’s important to acknowledge that you don’t know everything and that you could always know and do better. For me, I want to pay less attention to this practice of “resistance” and try and open myself to alternative ways of seeing, interacting and relating. The excerpt asks something which I would’ve once considered impossible and without sense – to resist and love, to resist and be open at the same time. It demands a revision of what it means to be both “resistant” and “vulnerable”. I still don’t entirely understand how to manifest that but that shouldn’t stop me or anyone else from trying. In this task of direct “resistance” whereby I close myself off not only to the evils of this world but everything else, where I am solely defined by this tension, this resistance, I deny myself the opportunity of receiving and being open to the potential of alternative worlds of relation.

J: You bring certain visualisations of masculinity across both the Dutch and the Caribbean contexts into relation with one another in Bikkel through your movements, language and costume, as well as through subtleties like the music playing from within your pocket. Do you consider the complexity of the character as a form of resistance?

A: No, the complexity of sources that converge within Bikkel informs his own sense of conflict. What needs to be considered is that these characters emerge from certain social conditions that would have shaped them without conscience or consent. If you are impressionable then your world will shape you and you will trust that it shapes you “properly”. Then, when you’re confronted with the realization that a lot of what has made you, what has conditioned you, what you have learned, is suspicious, groundless, damaging or simply questionable, you are led to a crisis of character and a kind of disenfranchisement with the world that has gradually made you. For Bikkel, specifically, it is this reckoning with this given image, these given expectations of masculinity, and the crisis of trying to unlearn this given shape, this given texture of roughness and hardness. The “resistance” per se is the crisis of this realization, and the swell of conflict responding to this mischaracterization; the realization that your world has betrayed you and your image.

J: Is there another context that you would be particularly interested in performing Bikkel?

A: The next step for Bikkel (which was actually the original idea but was delayed) is to walk him through Zuidplein in Rotterdam. It is where a shopping center, bus station and metro station converge in the South. When it’s busy, you can see a lot of guys dressed in all varieties, designs, colours and styles of tracksuits, bomber jackets, sweaters and hoodies, posed around. Though some are in transit, the space does seem to function as a meeting point where these style icons can collide and compete in this public posing off. I think Bikkel would enjoy this space.

J: You also screened a film during the event, Lookalook, which captured a performance held in Barbados earlier in the year. Lookalook calls out the violence that is elicited when a group of viewers are unable to name or understand something that they are looking at. Have you experienced a difference between the film being seen in Barbados versus the UK?

A: Not at Jerwood Space but the most vitriolic response I received when we screened the film during LADA screens in August was someone expressing their frustration in not knowing where Lookalook was performed or filmed, until Barbados eventually got mentioned. They were confident that my film and its script were not showing an accurate picture of Barbados, though they had admittedly never visited. Or, rather, the image I was posing did not agree with their expectations and preconceptions of Barbados and the wider Caribbean region. The fact that they took that as a point of frustration and not a point of transition, unlearning and revision concerns me but maybe I’m asking for too much. I’ve previously not seen the sense in performing Lookalook in London, as people avoid eye contact so desperately, but perhaps it would call for a new mythology of the character, getting Londoners to revisit a lost time when they used to look each other in the eye.

Ada M. Patterson, Bikkel (2018) Sensational Bodies, Jerwood Staging Series (2018). Image by Hydar Dewachi